This essay is a follow-up to the last week’s cover story.

Jaspreet Kaur

While it is necessary to understand the traditional architecture of Kashmir, especially the construction techniques, for its structural innovations, suitable for the seismic zone V, it is equally necessary to understand the physical and urban geography (urban form), especially in view of Srinagar being developed under Smart City project.

Srinagar, the summer capital of Jammu and Kashmir, and the oldest city of the Valley, has retained its prominence through various eras. The nature and character of the place, the response to climate, overlapping religious practices helped in fashioning the urban pattern, quite unlike other river-based and mercantile cities.

Urban History

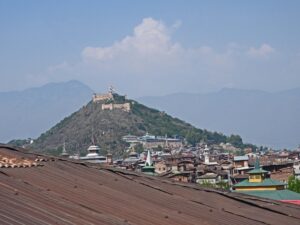

Although Srinagar is now known as a riverine city, it was founded around the Hari Parbat (Koh-e-Maran), away from the river and constant threats of flooding. Saleem Beg (Convenor, J&K INTACH chapter) adds that it is likely, that a few temples with their associated ghats (yarbal in Kashmiri) came up along the river.

The City of Srinagar is said to have been founded by Emperor Ashoka in 250 B.C. near Panderethan, three miles south of present day Srinagar. In the 6th century A.D., King Parvasena II founded the new city of Parvarapura around the hillocks of Hari Parbat. The city is said to have contained well-built wooden houses connected by numerous water canals and regularly arranged markets. Some temple ruins still exist in the Hawal-Soura belt. This city was destroyed by king Lalitaditya in 695 A.D.

Located mostly on the right bank of River Jhelum, which was a perennial water source and the most convenient trade and traffic route into the Valley, the city emerged first as a trading post, being on the Silk Route, and then developed into an urban centre. It is located on both the sides of the Jhelum River, (Vyeth in Kashmiri), at the base of Zabarwan Mountain range.

The city’s development was determined by the natural barriers formed by the River on the north, Anchar Lake on the west and Dal Lake on the east. The other barriers were the Hari Parbat and Shankracharya (Takht-i-Sulaiman) hillocks, where to date exists the most densely built up area of the city.

The subsequent extensions of the cCity were also in the vicinity of these landmarks. Till the 19th century, Gojwara – Eidgah-Chattabal corridor in the north and Maisuma-Shergarhi corridor in the south marked the physical limits of the city.

The advent of the Muslim Rule in the early 14th century marked the synthesis of a new culture, when, and until the rule of Maharaja Ranjit Singh, it was called Shehar-i-Kashmir (the City of Kashmir) marking its political and cultural pre-eminence in the region.

The City’s overall form continued as an organic and linear development principally along River Jhelum and later around numerous canals and streets. Up until the first Cart Road, which was the Baramulla-Srinagar Road in the 19th century, the City remained dependent on water borne transport on the River Jhelum and various canals.

As the city developed, residential quarters got organised on the basis of craft/ trade/ profession, and even family clans, as mohallas, like the Sheshgari Mohalla, Qalamdanpora, Thanther Mohalla, Rangher Mohalla, Boher Kadal, Bundhuk Khar Mohalla. Examples of mohallas organised around family clans are Banday Kocha, Razdan Kocha, Bhan Mohalla etc. The mohalla of Maleech Mar, near the khanqah of Bulbul Shah is believed to be of the earliest Muslim community that settled in Kashmir.

A mohalla was typically made up of thirty or more residential units with an associated mosque or temple. For those mohallas situated on the banks of Jhelum or its canals, the ghat would be an important urban feature, serving as the main hub for goods being transported. The ghats were also the focal points of socio-religious activities. In addition, the ghats were used to wash namdahs (rugs), ruffle, wazwan utensils and to soak wicker before weaving it into baskets.

Though located on the river bank, old Srinagar does not entirely open onto the river. The riverfront is lined with several ghats on both the banks. However, their scale is mostly insignificant. As compared to other river cites like Varanasi, the ghats in Srinagar do not form a continuous linear edge. These are isolated stretches at the periphery of individual mohalla, lane or kucha with no link to the other ghat.

The residences of the wealthy traders and rich landlords were generally located on the riverfront and dominated the urbanscape by their sheer size. Despite their scale, the overall physical character of the mohalla along the riverfront was of a single cohesive unit with projecting wooden balconies, intricate lattice work window screens and birch bark roofs, covered with iris and tulips.

Sameer Hamdani (author of The Syncretic Traditions of Islamic Religious Architecture of Kashmir (Early 14th–18th Century)writes: “The specific location of khanqahs and shrines, on prominent turns of the riverfront, accentuates the visual impact of these buildings, rendering them into major urban landmarks figuring prominently in the panoramic view of the river.” Besides these, the city has some prominent shrines of monumental scale with large open spaces around them. Over a period of time, the khanqah (ribats in Arabic) became the ‘relegio-temporal place of the community, independent of the palace’.

Though Srinagar primarily served as an administrative centre of Kashmir, its survival was dependent on trade and commerce. The bazars, the kharkhanas and the tchaat haal (training centres), were the pulsating centres of the city. This in turn supported the wealthy, the artists, writers and the likes.

Sultan Zain-ul-Abidin (1422-1474 CE) extended the city to the north of Hari Parbat. The development of the City remained confined to mostly between Ali Kadal-Hari Parbat and the Habba Kadal even after Sultan Abidin.

(The two important landmarks of Srinagar, Jamia Masjid and Makhdoom Sahib, form a visual axis at the foothills of Koh-e-Maran. The city of Srinagar grew around these landmarks and is still at its densest here) *Pic: Jaspreet Kaur*

It was during his reign that the first permanent bridge at Alauddin Pura, known as Zaina Kadal (kadal meaning bridge) was built. Thereafter the city grew on both banks of the river.

During the rule of Sultan Yousuf Shah Chak (1579-1586), the Capital was shifted to the left bank. The palace which occupied the area currently housing Shah Mohalla-Tankipora, was protected by a newly dug moat, Kut Kul, which continues to be used today as a means of water transportation.

The Mughal rule did not affect the overall settlement pattern of the city. Nagar-Nagar, Akbar’s provincial capital located on the northern foothills of Hari Parbat within the encircling stone ramparts (kalaye), remained a city within a city, and out of bounds for the general public. During Shah Jahan’s rule, Ali Mardan Khan, the Subedar of Kashmir raised a stone embankment wall around the Tsunth Kul. However, the most outstanding legacy of the Mughal rule in Kashmir are the Mughal Gardens (baghs) and the baradaris. Said to have numbered 800 during their rule, less than a dozen survive today.

The Afghan ruler, Amir Khan, built the Palace-Fort complex of Sherghari and Amira Kadal near Shaheed Ganj. Shergarhi (Now the Old Secretariat), served as the residence of the Afghan rulers and then the Dogras. Shergarhi extended the city further south, and by the time of the Dogras and the British (in the 1880s), the Residency was built on one side of the Jhelum, while Raj Bagh and Gogji Bagh were established on the opposite bank.

From the rule of Maharaja Ranjit Singh till the Dogra rule, the city saw a considerable European influence. Institutions like schools (Burn Hall, Tyndale Biscoe School), colleges (S.P. College), hospitals and factories were built. European staff and visitors were initially housed in tents in Chinar Bagh and Sheikh Bagh close to the Residency. Later, they colonised the Dal Lake with extended stays in houseboats.

The Srinagar Municipality was established in 1886.

In later years, the rich began moving out from the congested old city to the new suburbs. Late 19th to 20th century saw the migration of people from the inner core to the new suburbs: Balgarden, Karan Nagar, Samander Bagh. New residential areas came up in low-lying areas such as Bemina, Chanapora etc. A portion of Karan Nagar in the name of Deewan Bagh was the first declared civil colony in 1942 by the former princely state government of Jammu and Kashmir.

The Lal Chowk commercial core of the city came up during the British period. The square was given its name by left-wing activists who were inspired by the Russian Revolution as they fought the princely state’s Maharaja, Hari Singh. The clock tower at Lal Chowk, a major landmark of the city, was built in 1980.

The first motorable road, near the Bund, on the right bank of Jhelum, was constructed in the early 20th century.

River, Lakes and Wetlands

Srinagar was once called the Venice of the East, with several canals, like the Nallah Mar, intersecting the city. It grew along the River Jhelum and around lakes and wetlands within and surrounding the city. These include the Dal Lake, Nigeen Lake, Anchar Lake, Khushal Sar, Gil Sar and Hokersar Wetland. Of Srinagar, Rudolph Langenbach writes: “Srinagar lies on one of the most waterlogged soft soil sites for a capital city in the world.”

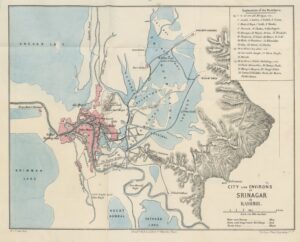

*1887 map showing the extent of Srinagar city and its environs.* Source: Wikipedia (Journals kept in Hyderabad, Kashmir, Sikkim, and Nepal. Edited, with introductions, by R. C. Temple)

River Jhelum has shaped up the ecology, economy and the lifestyle of the inhabitants of the Kashmir valley and Srinagar city. The whole length of the Jhelum from its source (Verinag spring in south-east of Kashmir Valley to Baramulla (North-west) is 150 Kilometres. The fall of the river is just 18 metres in 113 Kilometres. All along its course, the river is characterized by the sluggish flow of main Jhelum river and of its 24 tributaries, draining from the slopes of Pir Panjal and Himalayan ranges. The river passes through the city and meanders through the valley, moving onward and deepening in the Wular Lake.

The city is known for its seven old bridges on the Jhelum, connecting the two parts of the city. The other two, Zero Bridge and Abdullah Bridge were added in the 50s and the 90s respectively. The smaller ones include the Lal Mandi Footbridge, Budshah Bridge and New Habba Kadal Bridge. The older bridges were entirely made of Deodar wood, apart from heavy rocks used to add weight to the foundation.

The Dal Lake is located within a catchment area in the Zabarwan mountain valley, in the foothills of the Shankaracharya, which surrounds it on three sides. The main basin draining the lake is a complex of five interconnected basins with causeways – the Nehru Park basin, the Nishat basin, the Hazratbal basin, the Nigeen basin and the Brari Nambal basin. Navigational channels provide the transportation links to all the five basins. The average elevation of the lake is 1,583 metres. The depth of water varies from 6 metres at its deepest in Nigeen lake to 2.5 metres at its shallowest at Gagribal.

Pir Gh Hassan Shah (1832-1998) popularly known as Hassan Khoyihami (author of four volumes dealing with geography, politics and aspects of human life of Kashmir) has described the Dal Lake in detail. According to him the Sonalank island (3-Chinari) in the Bod Dal basin, in front of Hazratbal, was constructed by Sultan Zainul-Abidin with his Royal Palace, destroyed during an earthquake. During Mughal period, a sightseeing tower was also built on the island. Sultan Hassan Shah (1475-1478 AD) built another island called Rupalank (presently Char-chinari), destroyed during Sikh period.

The laying of floating gardens, islands for cultivation of vegetables had begun in the lake, however, the lake waters were said to be wholesome and calm with restricted zones for lotus stem (nadru) cultivation. During 1771-1774 CE, the governor of Kashmir, Amir Khan, renovated the Sonalank and drew the lake water to the Chinar tree and into the garden of the building through a Persian wheel. Hassan also states that the waters of the Dal Lake would flow into river Jhelum near Habba-Kadal. It was again King Zainul-Abidin who closed the outflow at Habba Kadal and instead dug out the Nallah Mar inside the city allowing thereby the flow of the lake water through the canal towards Anchar. Prior to it, an intervention was also made in 1413 CE by Sultan Sikander who constructed a bund on the Dal Lake from Nayidyar, Rainawari to Nishat bagh along with six bridges – Choudhry Kadal, Doodpathri Kadal, Tulkhan Kadal, Gani Kadal, Oont Kadal and Nishat Kadal. Only the Oonth Kadal has survived.

Saif Khan, the governor of Kashmir who ruled the valley twice i.e., 1647 CE to 1667 CE and 1668 CE to 1771 CE, built another bund from Khawjayarbal to Ashaibagh on Suderkhun (now known as Nigeen Lake). Consequently, the Dal Lake was divided into three parts: Bod Dal (in front of Hazratbal), Lokut Dal (expanse from Shankracharya to Nishat Bagh) and Suderkhun (situated in front of Hari Parbat). This was the beginning of the changes in the flow pattern of the lake. The large tracts of stagnant waters along the inshore areas were also created. Two additional islands were built which further obstructed the water movements.

The Boulevard Road was laid along the southwest part to improve communication which separated a large part of the lake creating marshy area along the fringes of Zabarwan mountains. It was in the 1970s when another road from Nishat Bagh to Naseem Bagh, as an extension to existing Boulevard known as Northern foreshore road was constructed.

Today Srinagar surrounds the Dal Lake on all sides – the University on one side and the Sher-i-Kashmir Convention Centre (SKCC) and the Royal Springs Golf Course on the other. With the Dal becoming a major tourist attraction, the Boulevard along the lake has become a highly commercialised area of hotels, eateries and souvenir shops.

While discussing the water bodies of Srinagar, it becomes imperative to discuss the Nallah Mar(Nallai Mar / Mar Kol), constructed by Zain-ul-Abidin in the 15th century. In addition to providing a second line of communication in the city, especially to the Eidgah and the Aali Masjid (built by Zian-ul-Abidin’s elder brother Ali Shah), the Mar canal also helped in draining the low-lying marshy areas surrounding the Dal Lake. Zian-ul-Abidin closed three streams of Brari Nambal and dug a new canal which ran from Baba Demb to Anchar Lake, passing through Eidgah into Khushalsar and Gilsar.He had fresh water brought from the Sind River into the city through the canal. A branch of this canal, Lachma Kul supplied water to the Jama Masjid till 1913. Another branch passed through Noor Bagh into River Jehlum.

Historian M A Stein, who translated Rajatarangini from Sanskrit to English, writes that a canal or a brook already existed there. It was perhaps called Mahasarat. Stein believes that Zain-ul-Abidin, also known as Budshah, might have revived the same canal and named it Nallah Mar.

Zian-ul-Abidin was also responsible for constructing the Nallah-i-Amir Khan linking Nigeen lake to Khushal Sar-Gilsar. This water channel provided an alternate route to the flood waters of Dal to escape to River Jhelum beyond the city limits. Development along the Rainawari canal also took place under him.

Sheikh Abdul Wahab Noori Ganai writes in his book ‘Fatheyat-e-Kubraviah’ that during old days the water of Dal passed through Mohalla Alla-ud-Din Pura via Brari Nambal. In the late 1960s, foreign tourists used to go to Ganderbal and Wullar Lake in dongas (large boats) through the Nallah Mar. Serving as an important transportation route within the city, the canal was paved with flat stones and bricks so that the water would be clean and its flow smooth, and was lined with shops and workshops on either side.

Many bridges were also laid over the Mar, namely Nowpora Kadal, Naid Kadal, Bohri Kadal, Saraf Kadal, Qadi Kadal, Rajouri Kadal, Kawdaer Kadal or Pacha Kadal, Dumb Kadal, Narwar (Buti) Kadal.

For centuries, the Mar regularly protected the people from floods by regulating level of different waterbodies it connected. However, during 1960s, the Nallah Mar was completely neglected and became a garbage disposal channel. It soon became a stinking spot and a major crisis, especially after the road transport, gradually set in.

The canal was erroneously filled up in 1975 and is now a market road with sewer lines below. This road did help in easing the connectivity issues to an extent but completely choked the water bodies connected to the Nallah Mar, leading to the stagnation of Brari Nambal lagoon and Dal Lake.

Zareef Ahmad Zareef, a poet and an oral historian, is of the opinion that the Mar lost its existence to the political rivalry between the ruling government and its political adversary within the city (between Sher and Bakra), resulting in Kashmir losing an important heritage. The road also made the monitoring of the downtown areas easier.

After the disastrous floods of September 2014, the importance of Nallah Mar came to the fore again. Many suggested that had the canal existed, it would have helped Srinagar drain faster and minimized the losses, especially in Dalgate – Munwar belt.

Srinagar also has some important wetlands in close vicinity. Hokersar, a Ramsar Site (as also Wular, Shalibugh and Hygam), is the most well-known of Kashmir’s wetlands, which include Narkara, Hygam, Wular, Shalibugh and Mirgund. These wetlands are important in regulating ecosystem services such as providing fresh water supplies, food products, fisheries, water purification, harbour biodiversity, and regulation of regional climate. These are also important as socio-economic support systems for the city inhabitants and valued as habitats of migratory birds that visit Kashmir valley from different continents of the world.

Threats and Challenges

Srinagar has embankment/bund walls on both sides of River Jhelum and also around the lakes. Most of these embankment walls are old constructions and they tend to get breached, owing to incessant rains and higher water discharge from its upper reaches, as was the case in September 2014. Some of the most affected areas were the low lying Shivpora, Indra Nagar, Raj Bagh, Jawahar Nagar, Gogji Bagh. Other areas that continue to face high flood risk include Bemina, Wazir Bagh, Lal Chowk, Nundreshi Colony, Shaheed Gunj, Madin Sahab, Kawdara, Zadibal, Idgah, Hazratbal, Lal Bazar, Karan Nagar, Chattabal, Batamaloo, Zainakot, Natipora, and Mehjoor Nagar. Several of these developments in the low lying and vulnerable areas came about as a result of the 1971 master plan.

The Dal Lake, with its current shoreline of about 15.5 kilometres, has shrunk considerably. In 1200 CE, the lake is said to have covered an area of 75 sq km. now reduced to 10.56 sq.km. Comparison of earlier maps to the existing extent of the Lake one can say that it’s more green than blue now.

Farther away from the shore, the lake is a mixture of mossy swamps, thick weeds, trash-strewn patches and floating gardens (raad) made from rafts of reeds. While it is believed that the local boatmen (Hanz/ Demb Hanz) are mainly responsible for changing land use and land cover of the lake, there have been several policy failures that have led to the deterioration of majority of the lake area.

Dr. Kundangar, former Director (R&D) JKLCM and professor of hydrobiology, explains that while several conservation projects, costing crores of rupees, have been carried out in the Dal Lake, the growth of hotels, houseboats and households near the lake have also been simultaneous.

The Anchar Lake is situated 14km from the city centre in the NW. The water supply is maintained by Sindh, a tributary stream of Jhelum and Achan Nallah in addition to springs along the vicinity of the lake. The lake has been affected by encroachments, sewage, and dumping of domestic wastes, and effluents from hospitals and wastewater treatment plants. The lake covered an area of 19.54 sq.km in 1894, which is now a mere 4.26 sq.km.

Gilsar and Khushalsar are twin lakes in highly deteriorated condition located toward the northwest of Srinagar city. The lakes received waters from the Nigeen basin of Dal Lake via Nallah Amir Khan. The lakes have been encroached upon at many places with illegal construction and landfilling These lakes receive sewage inputs estimated about 465 million litters per day.

Brari Nambal is a marshy lagoon. It has a narrow outlet on the western side and drains into river Jhelum through an underground channel. In 1971, it covered an area of 1 sq.km which reduced to 0.77 sq. km by 2002.

The wetlands used to act as buffers soaking flood waters but urbanisation, encroachments and other hydrological changes within these wetlands have reduced their water holding capacity, thereby, increasing the chances of flooding. Unfortunately, in recent times, wetlands have been termed as ‘wastelands’.

The Hokersar wetland, which is the largest bird reserve in the Kashmir valley, is situated in the Jehlum River basin. It has reduced from 18.75 sq.km in 1969 to 13.00 sq.km in 2008.

Narkara, a semi-urban wetland, situated on the outskirts of Srinagar, is basically a detention basin for surplus flood water arriving from the Doodhganga stream. This too, has shrunken to a great extent in the last 50 years. A no-construction zone has been earmarked along its banks. In spite of this regulation, a considerable development has taken place.

Over the past few decades there has been unabated urban expansion and change of land use and land cover on both sides of the river Jhelum. Srinagar city built-up area increased from 2.45 % in 1961 to 39.08% in 2013, with an overall increase of 36.63%.

As per the Census of India (2011), the population of Srinagar city was 12.2 lakh. The current metro area population of Srinagar in 2022 is 16.6 lakhs, with an average annual increase of 2.3%. The United Nations population projections indicate that by 2035 population of Srinagar will be 22.2 lakhs.

Given the mismanaged situation, due to various socio-economic and political reasons, residents continue to look for land where there is none, eventually making way and landfilling ecologically sensitive, low-lying regions of the city. However, it is largely the administrative and planning policies that have resulted in the precarious amoeboid growth of the city. (cover pic: Jaspreet Kaur)

Jaspreet Kaur is a New Delhi-based architect and urban designer.