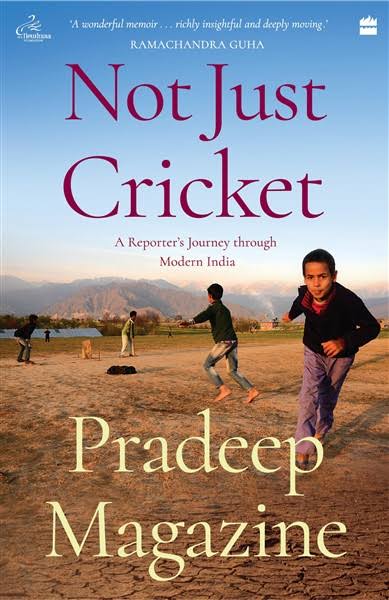

Series of excerpts from Not Just Cricket by Pradeep Magazine.

As I was seeking answers to what had actually transpired during that period and whether Jagmohan, as his detractors said, had facilitated Pandit migration instead of stopping them, I asked Bakaya for his version of the events during that harrowing period. ‘I had hundreds of Pandits who trusted me coming over seeking guarantees for their security and threatening to otherwise move out of the Valley,’ recalls Bakaya, saying that some of the Pandits described a sense of fear caused by chants from mosques asking Pandits to leave. There were anonymous threats and intimidatory posters that made them want to leave. According to Bakaya, he did convey his apprehensions to Jagmohan and requested him not to allow the Pandits to move out of the Valley but instead ‘create temporary camps for them outside Srinagar, guarded by the security forces till they felt safe to return home’. He says Jagmohan was not in a position to spare army men to safeguard those camps and there was a worry that the Pandits could have become sitting targets for the militants. In 2009, I had another opportunity to visit Kashmir, to do my first-ever report on a political event. That year, Sajjad Lone announced that he would contest the Lok Sabha elections as an independent candidate. Sajjad’s father was the well-known separatist leader Abdul Ghani Lone, who was killed by a militant in 2002 during a public rally. Sajjad was articulate and spoke in fluent English, never mincing his words in advocating for Kashmir’s independence from India on TV debates. He had inherited his political outfit, the People’s Conference, from his father. Until then, the party had boycotted elections, much like all the other separatist leaders and parties since 1987. But in 2009 he had decided to abandon that policy. From Kashmir’s point of view, it was a stunning development for a mainstream separatist to swear by the Indian Constitution and participate in its democratic processes. Being a Kashmiri Pandit, I found this an exciting scenario and I wanted to go to Kashmir to meet Lone and write an eyewitness account of his first rally. My employers agreed and I went on a short visit that had a lot of hectic travel and emotional churning. I travelled from Srinagar to Handwara town, home to the Lones and one of the hotbeds of militancy in the nineties. I had to take the Baramulla–Kupwara highway, a road not many would dare to take during the peak of militancy. I had two people accompanying me: a taxi driver called Ali Mohammed, who had driven many visiting journalists on their Kashmir assignments, and Waseem Andrabi, a photographer. Ali Mohammed was old enough to vividly remember those peaceful days when Pandits were an integral part of life in Kashmir, and he was of immense help in finding old connections and forgotten names for me. Andrabi, much younger and full of energy, represented a generation that had only lived under the shadow of guns, curfews, protests, terror killings and repression. During the three-hour drive from Srinagar, we regularly passed military convoys and many makeshift camps housing security forces. Soon, we reached the house where Sajjad’s secretary had asked me to come. It was the day when Sajjad was launching his campaign, one that many felt could be a turning point in Kashmir’s political history. I introduced myself as a Kashmiri Pandit on a journey of rediscovery with no malice or hatred in my heart. Busy, distracted and on a tight schedule, Sajjad briefly said that he was happy to let me be part of his entourage for the day, which included few scheduled meetings in villages surrounding the town. That day, I saw first-hand how difficult it was for Sajjad to make people understand his turnaround from being a hardcore supporter of Azadi to now agreeing to swear by the Indian Constitution. Over the course of my interactions with him on that day and some other occasions since, I found him to be a pragmatic person. He said that after the 9/11 terror attacks in the USA, the world had changed forever. “Let us be realistic, we can now never get Azadi and have to look for options that allow us to live with dignity and respect,” he stated. He carried his late father’s walking stick everywhere to serve as a reminder to his people that he was carrying forward Ghani Lone’s legacy. Sajjad would emphasize in his speeches that he had not sold out to India but would now air their grievances in the Parliament. On the way to one of the villages, we had lunch at a local’s home, and later had tea at someone else’s home; in each place he did not forget to remind his assistants to take care of me. In one of the public meetings, he even forced me to sit on the makeshift stage with him, and told people that a Kashmiri Pandit from Delhi was among them and it was their duty to rebuild the old, broken bridges. Sajjad had married Asma, the daughter of Amanullah Khan, who is the founder of the Jammu and Kashmir Liberation Front, a militant outfit that advocated a Kashmir independent of both India and Pakistan. He was now walking a dangerous tightrope as his wife, a Pakistani citizen, was being denied a visa to come to India. The couple could not live together, and I could sense that a part of him wanted to live in a liberal world free of religious dogmatism. However, the more ambitious part of him wanted political power. In 2018, Sajjad would become part of the ruling Peoples Democratic Party and BJP alliance. He was even projected as a BJP supported candidate for the post of chief minister at one point. However, along with all mainstream Kashmiri political leaders, he was put under house arrest in August 2019 when the Modi government abrogated Article 370 that had given special powers to the state. Kashmir’s status was changed from a state to a Union Territory. Back in 2009, before my flight back to Delhi from Srinagar, I went on a tour with Ali Mohammed to those areas of Srinagar that I had known well. They were the places where our relatives had lived and I had often visited. I had heard that Rattan Rani, the doctor who had delivered me, had never left Srinagar. Despite her old age, she was still practising in the interior of the town near Habba Kadal, an area once largely inhabited by Pandits. I was keen to visit her, and thanks to Ali Mohammed’s efforts we traced her house in Tankipora. The Muslim caretaker of the house took me inside to a room where an old lady sat behind a desk. An almirah full of medicines stood behind her. According to the caretaker, her memory was fading and she was now no longer treating patients, something which she had not stopped doing even at the height of militancy. She had refused to move out of Srinagar, not heeding the requests of her children who were living outside the state to come live with them. Muslim neighbours and friends had taken care of the doctor who had tended to the medical needs of the larger Kashmiri community. I tried my best to help her recall a memory from over five decades ago: the Magazine family, a patient of hers called Raj Dulari and the birth of a child, who was now standing in front of her. She asked me to write down the names, which I did on a piece of paper. She smiled, though I doubt she could recall a past that I was trying to connect with. I came out of the house overwhelmed by many emotions. The frail old woman had withstood the onslaught of time and the traumatic upheavals of her homeland. She had had the courage not to flee and abandon her roots. I felt, somehow, we had betrayed her. (concluded)

Excerpted with permission from Harper Collins.