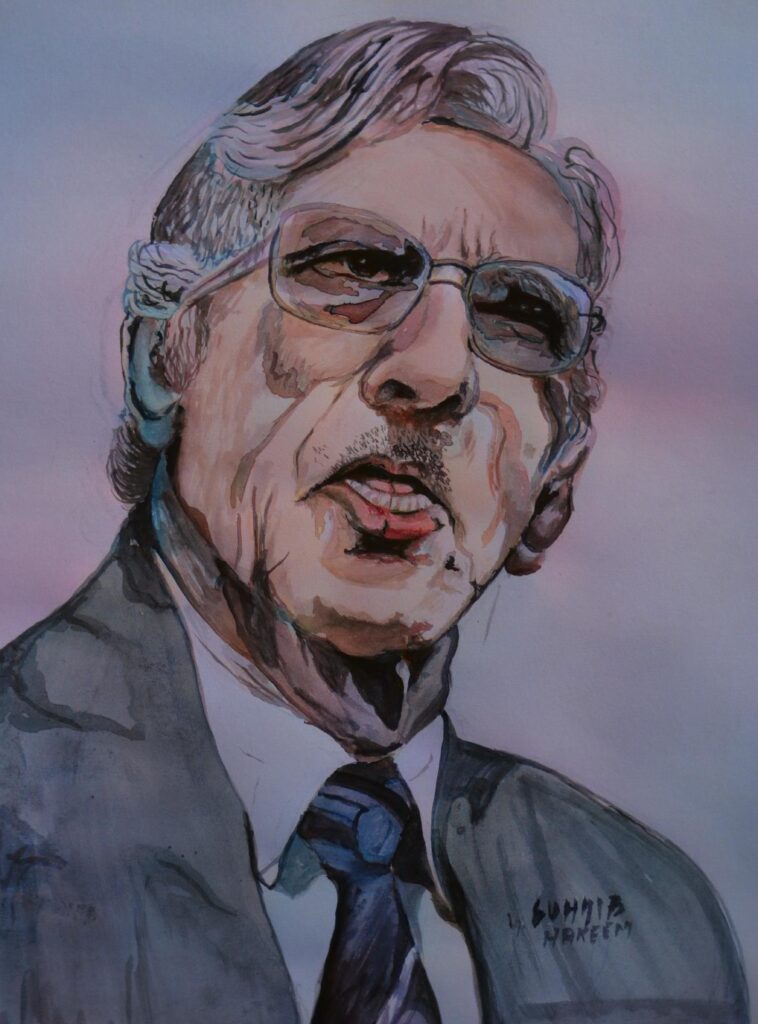

The Jnanpith winner was a lifelong campaigner for the Kashmiri language.

by Tariq Rashid

On the day of his passing, his poem Karav Kyah!—What Can We Do!—resonated with mourners as rich tributes kept pouring in for Prof. Rehman Rahi who breathed his last today in the wee hours at his Vichar Nag residence. The multiple award-winning bard had retired from active life. He was 98. Karav Kyah! is a lament portraying the helplessness of the people of conflict-ridden Kashmir. Rahi was often accused of not raising his voice in the turbulent nineties when the Kashmiris were at the receiving end of the ubiquitous violence.

Many believed his poem (Karav Kyah!) was his way of making up for his silence that dominated the public discourse.

“Many of Rahi’s critics questioned his silence during the traumatic times of Kashmir,” said Anzar Mir, a scholar doing research on Kashmiri poetry’s post-colonial diction. “But the fact remains, the poet’s pen always bled for the man on the street. Through his literary experiences, vision and translations, Rahi always spoke a commoner’s language in Kashmir,” he said.

Reverence for Rahi comes from his poetry of realism. The tall – both literally and metaphorically – and terse wordsmith quintessentially used his vision to speak about the valley and its people in their own language.

“If there’s no Kashmiri language,” Rahi explained to one of his students in the documentary titled Rahi by M.K Raina, “there will be no Kashmiri, and hence there will be no Kashmir.”

Kashmiri language is a nation in itself, Rahi would always say. “The language works like a unifying force. The scattered Israelis were unified by the idea of their language – Hebrew. It’s all about being conscious of one’s identity.”

Kashmir language wasn’t part of syllabus until Prime Minister Sheikh Abdullah introduced it from 1948 to 1953. But due to Abdullah’s bickering with New Delhi, the language couldn’t come out of its confines. “Sheikh Abdullah did come out of the prison,” Rahi said, “but our language is still languishing.” Rahi invoked Kashmiris’ love for their Sufi past and the works of Lal Ded and Nund Reshi.

It was the same love that made him a lifelong campaigner for Kashmiri.

In 2007, Rahi won India’s highest literary award Jnanpith for his anthology of poems, Siyah Rood Jeren Manz – Under the Dark Downpour. Earlier, he had been honoured with Sahitya Akademi Fellowship in 2000. As a young poet in 1961, Rahi bagged the sahitya Akademi Award for Nauroz-e-Saba, a collection of Kashmiri poetry.

Rahi is also a recipient of Padma Shri, India’s fourth highest civilian award.

After receiving the Jnanpith Award, an emotional Rahi said: “It is the recognition of the language of our speech and thought. I’m happy and sad today. Happy, because I was honoured. Sad, because my people continue to be in distress.”

In his poetic works, Rahi employed unpretentious language to summarize Kashmir’s situation driven by the identity. It’s this culture-centric poetry delivered in native language that identified Rahi with the people.

“Kashmiri words helped me to express my ideas with greater ease,” he once said. Perhaps that’s why his poetic expression is seen as a meditative enchantment of words.

The poet always wanted Kashmiri poetry to be at par with major languages of the world. He said in one of his interviews: “The modern concept of short poems in Kashmiri is on a par with English poetry.”

Exploring this literary contrast, scholar Aarizoo Majeed draws parallels between Rahi and TS Eliot in her research. The two literary giants, she argues, have dealt with the concept of modernism and modern man in their respective poems: Soan Gaam (Our Village) and The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock.

“The poets while working independently on the portrayal of the theme have excellently toyed with the senses of the readers whilst appealing the sense of imagination the most in trying to bring forth the problems of Modernization,” says Aarizoo whose paper was published in International Journal of English Literature and Social Sciences (IJELS). “Like Eliot, Rahi talks about the disillusionment of man, his concerns, his social status, his feelings of being a nobody.”

Apart from Eliot, there are shades of Nietzsche’s philosophy in Rahi’s rhymes. The title of his anthology Farmove Zartushtan was, in fact, inspired from Nietzsche’s Thus Spoke Zarathustra. “And then,” says English scholar Nazish Ali, “you find Camus’s anguish on social realities in Rahi’s poetry.”

Born as Abdur Rehman Mir on May 6, 1925 in Srinagar’s downtown area of SR Gunj, Rahi was brought up by his maternal uncle after his father passed away. His enrollment in the historic Islamia High School of Rajouri Kadal saw him frequenting a bookseller for literary grooming. Apart from his daily brushes with some legends engaging in literary talks at the shop, the bookseller would order poet Iqbal’s complete work from Lahore for the voracious reader. This is how Rehman Mir became Rehman Rahi.

But as 1947 drew closer and the young Rahi continued to shuttle between his shop-school and speculative streets, he decided to found the Kashmiri Cultural Congress. The creative initiative earned Kashmiri literature a recognition in line with other major languages of the Indian Subcontinent. Post-partition, as Rahi completed his masters in Persian and Arabic, he got a job as a clerk. But given his coming of age literary prowess, he quitted and joined the Congress mouthpiece, Khidmat. Maulana Masoodi, the patron of the publication, wanted Rahi to write against anything but politics. For a change, Rahi obliged, as “the stooges and snoops of Jashn-e-Kashmir were hounding the dissidents like mites.”

In his stint as a scribe with Khidmat, Rahi was drifting towards the popular Red Movement and became a sparkplug of the Progressive Writers Association of Kashmir. As part of the Left-leaning Bloc, Rahi produced poetry on humanism, universality, modern outlook and revolutionary ethos. He soon established himself as the most prominent Kashmiri poet. He raised the human tragedies in Yemberzal – Daffodils – and O’ Khodaya – O’ God!

“Life is nothing but dark downpour,” he declared based on his belief on Existentialism and the theatre of absurd. Among Rahi’s comrades were literary giants like Dinanath Nadim, Akhtar Mohiudin and Amin Kamil.

At about the same time, Rahi taught Persian, Urdu and English before taking over as the first Head of the Department of Kashmiri at the University of Kashmir from where he retired in 1985. The University of Kashmir’s anthem, Yee Mouj Kasheeri, is authored by Rahi.

Rahi is hailed for creating idioms of the modern Kashmiri language and working on the Encyclopedia of Kashmir. Apart from his major translations, he’s celebrated for guarding the Kashmiri language from Persian and Urdu influences.

Paying homage to Rahi on his demise, noted satirist and social activist Zareef Ahmad Zareef called him a “selfless mentor.” Rahi, he said, was the last standing soldier of the Kashmiri language.