The 368-page book is a compelling read.

Col. Sushil Tanwar

To most of us, the mere mention of the word ‘Pashtun’ creates an image of mystique and intrigue. Are the Pashtuns violent or are they benevolent? Are they oppressed or are they opportunists? Are the Pashtuns men of honour or masters of survival? What do they value more? Tribal traditions or religious faith?

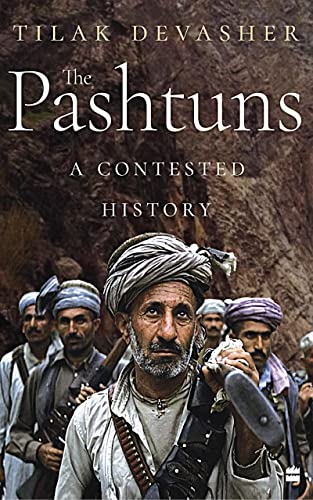

These are complex and intricate questions with unsure answers. Tilak Devasher, one of the most prolific commentators within the Indian strategic community, has attempted to demystify these multiple layers of Pashtun identity in his latest offering, The Pashtuns: A Contested History.

Ever since its release a couple of months back, this book has received much praise and critical acclaim. The most striking feature of the book is that the author has skillfully combined his vast experience and knowledge with extensive research and lucid expression.

Spread over seven sections, The Pashtuns offers a comprehensive view into the culture of the Pashtuns and the geostrategic realities that they live within.

The past and the present of Afghanistan, and by extension that of the Pashtuns, has been subjected to various external influences. British imperialism in the 19th century, the Soviet invasion in the eighties and the American intervention post 9/11 are well known and the author has dwelled upon them in considerable detail.

Each of these military campaigns was characterized by initial tactical success and a subsequent strategic withdrawal. As Tilak points out, every cycle of war invariably brought a 3D effect on the Pashtuns: death, destruction and displacement.

The book also highlights some key insights into the traits and character of Pashtuns, the most important being their inability to stay united and a propensity to close ranks only when confronted by foreign threats.

The legality and relevance of the Durand Line, along with various strands of relationship between Pakistan and Afghanistan, is also covered in the book. The idea of Pashtunistan has been discussed in detail. Although, the author concedes that even Khan Abdul Gaffar Khan, the Frontier Gandhi, was ambiguous about the exact idea of Pasthunistan.

One might, therefore, differ with the author on this issue. After all, Pashtunistan, as of now, is a notional and abstract concept. What does it actually imply? Does it mean a separate province for Pashtuns in Pakistan? Does it refer to a breakaway state to be carved out of Pashtun dominated areas of Pakistan? Will it be an independent nation comprising Pashtuns living on either side of the Durand Line ? Does it indicate a greater Afghanistan which assimilates the Pakistani Pashtuns?

None of these is possible unless Afghanistan or Pakistan, or both, implode and are balkanized. And this doesn’t appear realistic, at least as of now. One can however never be sure of what will happen in the future.

Pashtunistan will, therefore, remain an imagination, a leveraging tool for Afghanistan and a constant source of insecurity for Pakistan. It is precisely why this fault line between the two neighbors needs to be studied and monitored.

There have been many earlier works on the Pashtuns, most notable being ‘The Pashtun Question: Unresolved Key to the Future of Afghanistan and Pakistan’ by Abu Bakr Siddique, a Pashtun journalist from Waziristan. His principal argument is that the “failure and unwillingness of both Afghanistan and Pakistan to absorb Pashtuns into their state structures and assimilate them in political and economic fabric is the root cause of instability in the region.”

Devasher builds his case on similar lines and proposes the need for socio-economic development of Pashtuns and the strengthening of the tribal structures which have probably been diluted over the last few decades.

Pakistan, of course, has constantly tried to undermine the Pashtun nationalism internally by undertaking various measures of mainstreaming them – one of them being their representation in the armed forces. The issue, nevertheless, continues to be a constant source of tension across the Durand Line as is evident in the recent attempts of Taliban to disrupt the construction of the border fence.

The Pashtuns is a relevant and contemporary work which will certainly appeal to those who have an interest in the region. One, however, feels that the inclusion of a few maps and charts explaining various provinces, agencies, ethnicities etc would have made it easier for a layman to understand the geographical dynamics. Similarly, a consolidated timeline giving the sequence of major events would also have been helpful.

Despite these minor omissions, the 368-page informative book is, undoubtedly, a compelling read.

Colonel Sushil Tanwar is a senior fellow with Center for Air Power Studies (CAPS), New Delhi. He is an avid reader and writes regularly on issues of national security.