Like the classical nudes and seminude sculptures of the West, Daagh infused his poetry with an element of eroticism.

Salim Arif

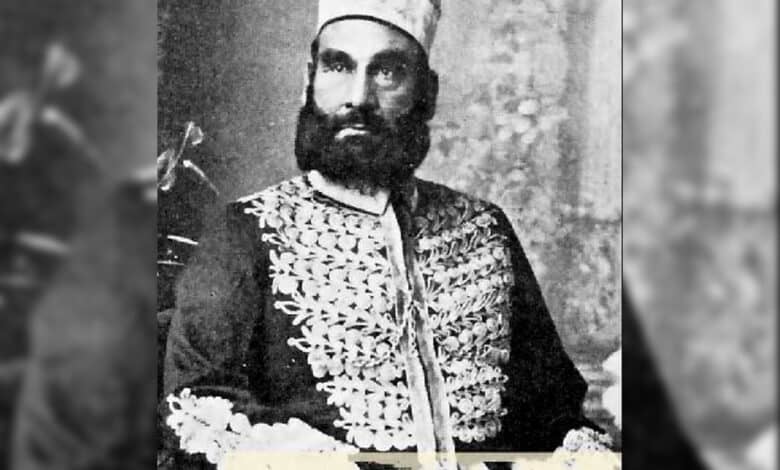

Known as the poet of love, Daagh Dehlvi remains the last of the classical Urdu poets who traversed various shades of ishq-e-majaazi (physical love), leaving behind a body of work that carries an underlying ocean of feelings and emotions. Shayar-e-Mashriq Allama Iqbal commemorated and acknowledged this master of Modern Urdu Poetry as his mentor in transmission of sensibility and sensitivity. He said:

Janaab-e-Daagh Ki Iqbal Ye Saari Karamat Hai

Tere Jaise Ko Kar Dala Sukhandaan Bhi Sukhanwar Bhi

(It is to the credit of Daagh, Iqbal

That he made someone like you a scholar and poet)

Before he became Daagh Dehalvi, Nawab Mirza Khan would have been executed or lost at a young age but for his mother, Vazeer Begum, who managed to keep him safe when his father Shamsuddin Khan was hanged on suspicion of conspiring against a British officer. Living in his maternal aunt’s house and different other places, Daagh was around 5 years then, and his mother found it hard to make ends meet.

His mother had children from her earlier and later relationships and marriages that included a daughter with an Englishman. After a few years, she finally married Bahadur Shah Zafar’s son and heir to Mughal throne, Mirza Fakhru, in 1842 and they all moved into the Red Fort as part of the royal family. From Mirza Fakhru, his mother had another son, Mirza Muhammed Khursheed.

The formative years of Daagh Dehlvi were spent in the royal residence and he lived a luxurious life for the next twelve years. His education at Qila-e-Mu’alla (The Red Fort) and grooming had the stamp of royalty. Very soon, he developed a taste for writing poetry and got the privilege to refer it to Ustad Zauq and Mirza Ghalib the royal mentors of Emperor Bahadur Shah Zafar. He started reciting poetry from a young age in poetic symposiums of the Red fort and beyond. Senior poets like Ghalib, Momin and Shefta were pleasantly surprised to see the prodigious talent of this young poet and acknowledged his flair for words. Ghalib marveled at this couplet of Daagh where he has used the oft repeated metaphor and image of Shamma (the candle) and Parwaana (the moth) with a changed context that creates a surreal poetic appeal.

Rukhe Raushan Ke Aage Shamma Rakh Kar Vo Ye Kehte Hain

Udhar Jaata hai Dekhen, Ya Idhar Parwana Aaata Hai

(Placing a candle in front of his glowing face, he says

Let us see if the moth goes to the face, or comes to the candle)

Ghalib credited Daagh for nurturing Urdu language in particular and would ask him to compose ghazals on the same metre (rhyme-scheme) as some of his own ghazals.

Playing with witty words and phrases and their skillful arrangement in his couplets, Daagh observed simplicity in his approach to the content of his ghazals. Acknowledged as a master who nourished and cultivated Urdu to make it independent of Persian and Arabic vocabulary and diction, Daagh took pride in the language he used in his poems that created a phonetic and contextual aura.

Urdu Hai Jiska Naam Hameen Jaante Hain Daagh

Hindostan Mein Dhoom Hamari Zuban Ki Hai

(We know what Urdu is, Daagh

Our language is applauded all over)

With a poet king like Bahadur Shah Zafar at the helm, regular interactions with poets, musicians made a huge impression on a young Daagh in his days at the Red Fort. Unlike his most other contemporary poets who were dependent on stipends for survival, Daagh led a cushioned life inside the Qila-e-Mu’alla, devoid of everyday concerns that other poets encountered. Besides, the relaxed and indulgent norms of life at the fort made interacting with maidens and women of charm an everyday affair. Daagh had an early initiation into adulthood where inhabitants of Salateen quarters (An enclosed area for descendants of several families of royal lineage) would often engage with immediate royal family on festivals and other such occasions. These opportunities were many, attracting a large number of poets, musicians, artists, craftsmen and courtesans from outside too. In the lanes and alleys of Shahjahanbaad, outside the fort, interacting with courtesans became a favourite pastime of men. Groomed in sophisticated manners, poetry and music, the courtesans of Delhi created an institution that rich men found fit to patronise as an aristocratic indulgence. Poetry of Daagh had been impacted by all this and was used extensively later by the desire of meeting the beloved in private – a woman desired by many. Description of various physical facets of a young girl, unrequited love are themes that are recurring in Daagh’s poems. Moving freely among ladies of pleasure, looking for sensuous pleasures, and obstructions in meeting them in private, find frequent mention in poems and couplets of Daagh.

Dee Shab-e-Vasl Moazzin Ne Azaan Pichhli Raat

Haaye Kambakht Ko Kis Waqt Khuda Yaad Aaya

(Call for the prayer came last night of communion with the beloved,

What an ungodly time to remind us of the Almighty)

The lover in his poetry expresses his love with an admission of lust and has no inhibitions about his amorous disposition. Devoid of any metaphysical or philosophical strain, the love of his protagonists is of an immediate physical level. Like the classical nudes and semi-nude paintings and sculptures of the West, Daagh infused his poems with an element of eroticism. But it is to the credit of Mirza Daagh that his love poems have inherent aesthetics that save them from becoming pulp-poetry. For Daagh, the female form and beauty is an important part of life’s romance, and one has to experience life in its full bloom and celebrate.

With the death of Mirza Fakhru in 1856, Daagh had to leave the secure life of the Red Fort as a result of palace intrigue and manipulations of Zeenat Mahal, the young wife of a very old Bahadur Shah Zafar. After the 1857 mutiny, Daagh left Delhi for nearby state of Rampur that was friendly with the British. Daagh, by then, had become a popular poet with his fame reaching far and wide. The Nawab of Rampur, Yusuf Ali Khan Bahadur, offered Daagh a respectable position at his court with a regular salary. The royal patronage was continued by Yusuf Ali Khan’s successor, Nawab Kalb-e-Ali Khan. Daagh grew prosperous with a comfortable life during his long stay at Rampur. It was here at the annual festival of Rampur in the Benazir garden that he got smitten by a courtesan-poet Munni Bai Hijab who, it is said, had an eye on the wealth of Haider Ali, younger brother of the ruling Nawab. Hijab was a capable poet and singer who got charmed by Daagh’s poetry and personality. Their relationship reached a point where Daagh got obsessed with Hijab who knew where her priorities lay. Hijab had fascination for Daagh who was now in his middle age, but was not willing to let go of Haider Ali and other resourceful men. She kept the romance alive with Daagh, making him travel all the way to Calcutta and propose without success. Faryaade Ishq – The Plea of Love – his

masnavi (a long poem) has a portrayal of this episode of his life. The period of Daagh ‘s life in Rampur was very productive and he was by now the most popular poet of Urdu. It was during these years that Daagh also composed most of his poems of melancholy. After the death of his main benefactor, Nawab Kalbe Ali, Daagh decided to move to a much bigger state of Hyderabad, which was then under the rule of the Asaf Jahi Nizams at the peak of their glory. After a period of struggle to make his mark in the city, Daagh was finally appointed at the Hyderabad court as a mentor to the ruling Nizam, Mahbub Ali Khan, in 1891. He lived a life of luxury in Hyderabad, working at a handsome honorarium. He was honoured with titles like Dabir-ul-Mulk, Fasih-ul-Mulk and Bulbul-e-Hindustan by the Nizam. Daagh once again went looking for Munni Bai Hijaab in Calcutta who, by now, was a devout Muslim. He persuaded her to divorce her musician husband and come to Hyderabad and marry him. After some time, their relationship turned bitter and Hijab had to leave him. Daagh Dehlvi passed away after a paralytic stroke on 17th March 1905 at the age of 73, leaving behind Gulzar-e-Daagh, Aftaab-e-Daagh, Mahtaab-e-Daagh and Yadgar-e-Daagh as four anthologies of ghazals of more than16,000 couplets.

He composed some qasida (Ode) and rubaee (four-line stanzas) too. Usage of everyday words and phrases, with a simple depiction, was distinctive of his style. Daagh’s poetry is appealing with a native idiom and a strong Sufi undercurrent. He synthesised the elements of Delhi and Lucknow schools of poetry.

Endowed with an intense romantic fervor, Daagh Dehalvi wrote poetry in the colonial period of the 19th Century that remains an iconic sample of a distinct voice for Urdu speaking masses till today. Apart from his disciples like Seemab Akbarabadi, Jigar Muradabadi and Ahasan Marharavi, one can find traces of his diction in poets like Hasrat Mohani and Firaq Gorakhpuri besides several others. It would not be erroneous to say that after the demise of Mirza Ghalib, Daagh remains the most gifted and influential poet of his era.

Salim Arif is a National School of Drama (NSD) alumnus credited with bringing Urdu back into the mainstream Indian theatre.