He was the first Indian to receive the Pritzker Architecture Prize, referred to as the Nobel Prize of Architecture.

Jaspreet Kaur

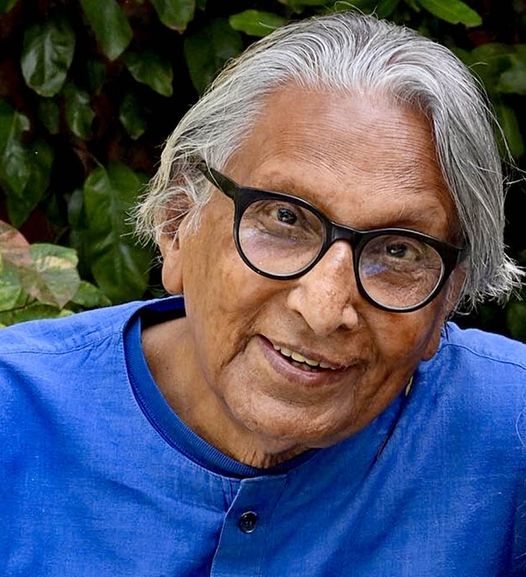

India’s most celebrated architect and founder of Centre for Environmental Planning and Technology (CEPT), B.V. Doshi, exemplified a life well lived and shall always be remembered as one of the great souls of India. Rest in peace!

Balkrishna Vithaldas Doshi, died in Ahmedabad today. He was 95.

Fondly called BV Doshi or just Doshi, he will be remembered by all whose lives he touched. We, as students of CEPT, are eternally indebted to him. We will miss his infectious enthusiasm and humility that touched us all so deeply. Never to forget the students he taught or met, he would greet us whenever and wherever we met him, years after we graduated. A great loss to all of us whose lives and works he has touched. He was our friend, philosopher and guide. His passing marks an end of an era.

In its tribute to the legend, Architecture Digest of India posted: “A master wielder of form and light, Doshi has left an indelible legacy. A loving husband, father, grandfather, and a true inspiration to the people of the country.”

Born in Pune, in 1927, into a family that was involved in the furniture industry for two generations, Doshi studied architecture in Mumbai at Sir J.J. School of Architecture in 1947. In 1950, he travelled to London, where he met Le Corbusier and, for the next four years, Doshi worked in the famed architect’s studio in Paris. He returned to India to oversee the construction of some of Le Corbusier’s projects, including the Mill Owners’ Association Building (1954) and the Villa Sarabhai in Ahmedabad (1955).

He eventually settled in Ahmedabad, where he designed his own residence (1963), named Kamala House after his wife; his studio, Sangath (1980); and some of his most important projects. In 1956 Doshi founded his own practice, Vastushilpa, which he later renamed Vastushilpa Consultants.

Doshi’s architecture is seen in some of the most iconic buildings in India. The firm worked on more than 100 projects throughout India, including a collaboration with Louis Kahn on the Indian Institute of Management Ahmedabad (1962). Other projects include the Indian Institutes of Management in Bengaluru and Udaipur, the National Institute of Fashion Technology in Delhi, along with the Amdavad Ni Gufa underground gallery , the Centre for Environmental Planning and Technology, the Tagore Memorial Hall, Institute of Indology and Premabhai Hall.

Known for his pioneering work in low cost housing, Doshi became one of the most influential architects of post-independence India, fusing international modernist principles with a deep reading of local vernacular traditions. His understated buildings adapted the principles he learned from working with Le Corbusier and Louis Kahn to the needs of his homeland. In considering India’s traditions, lifestyles, and environment, Doshi designed structures that offered refuge from the weather and provided spaces in which to gather. He wrote of the need for architecture to “reflect social lifestyles and spiritual convictions” and referred to “constant elements of Indian architecture: the village square, the bazaar, the courtyard.”

His Aranya Low Cost Housing, built in Indore in 1989, accommodates more than 80,000 people in a complex of houses and courtyards, woven with a labyrinth of internal pathways, with the homes designed with extension and adaptability in mind. It won the Aga Khan award for architecture in 1995, praised for its integration of mixed-income groups. He planned the Vidhyadhar Nagar, a satellite city of 350,000 people close to the old city of Jaipur, in 1986.

In 2018, he became the first Indian to receive the Pritzker Architecture Prize, referred to as the Nobel Prize of Architecture, which was founded in 1979 and has celebrated such figures as Oscar Niemeyer and Zaha Hadid.

“Balkrishna Doshi has always created an architecture that is serious, never flashy or a follower of trends,” said the Pritzker jury in its citation, praising his work as embodying “a deep sense of responsibility and a desire to contribute to his country and its people through high quality, authentic architecture.”

On receiving the Pritzker news, Doshi said: “I owe this prestigious prize to my guru, Le Corbusier. His teachings led me to question identity and compelled me to discover new regionally adopted contemporary expression for a sustainable holistic habitat. My works are an extension of my life, philosophy and dreams trying to create treasury of the architectural spirit.”

In 2019, a retrospective of Doshi’s work, ‘Balkrishna Doshi: Architecture for the People’, was organized by the Vitra Design Museum, Weil am Rhein, Germany and Wrightwood 659, a private exhibition space in Chicago. In addition to the Pritzker, Doshi was made an Officer of the Order of Arts and Letters (2011), France’s highest honour for the arts, and he was the recipient of the 2022 Royal Gold Medal from the Royal Institute of British Architects, an annual award given to those who have contributed to the advancement of architecture.

He had described his own office, Sangath, which means ‘moving together through participation’ as “an ongoing school where one learns, unlearns and relearns.”

The buildings are half-buried in the ground, where they are better protected from heat, dust and monsoons, while the vaults are made of ceramic pipes, covered in concrete and broken white tiles, providing insulation from the sun while shedding water in the rainy season. As modernist historian William Curtis puts it: “Sangath was on the knife edge between industrialism and primitivism, between modern architecture and vernacular form.”

In addition to addressing practical needs, Doshi’s work could also be playful, as seen in one of his most experimental projects, Amdavad Ni Gufa in Ahmedabad (1994). The art gallery features the colourful work of artist M.F. Husain within an underground space. The cavernous interior uses irregular columns and, like a cave, offers a cool refuge from the Indian summer. The bulbous roof, which is covered in a mosaic of white tiles is low enough to the ground that visitors can walk upon it, sit, and interact with one another.

He had been critical of the current state of architectural education and had said in an interview that most architecture schools are “looking at the body of a skeleton and not what is below the flesh.”

“Certain issues are timeless,” he added, “like how do you articulate space? Or how do you get the sunlight inside and work the shadows? … It’s a question of what affects you and what triggers in you a sense of being alive. I think that’s very important. The schools are not making people alive.”

He was a visiting professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Washington University in St. Louis, the University of Hong Kong, and other universities. He lectured extensively throughout his career and published his autobiography, Paths Uncharted, in 2011.

For us, though, as his students, the most memorable and impressionable project definitely has been the School of Architecture building, Ahmedabad. He founded the School in the 1960s with open-air classrooms and a focus on learning from context, which he led for 50 years. The school continued to grow in the following decades, expanding to include, among others, the School of Planning in 1970, the Visual Arts Centre in 1978 and the School of Interior Design in 1982. It was renamed as the Centre for Environmental Planning and Technology (CEPT University) in 2002.

He was the first founder Director of the School of Architecture, Ahmedabad (1962–72), first founder Director of the School of Planning (1972–79), first founder Dean of the Centre for Environmental Planning and Technology (1972–81), founder member of the Visual Arts Centre, Ahmedabad and first founder Director of the Kanoria Centre for Arts, Ahmedabad.

I am so fortunate that I got to spend so much time with him.

Jaspreet Kaur is an architect, urban designer, trustee Span Foundation & Lymewoods and consulting editor of Kashmir Newsline.