There is a need to revisit the issue of women’s rights not only in Iran but also in several other countries.

Dr. Sadaf Munshi

In her book ‘Iran Awakening: One Woman’s Journey to Reclaim Her Life and Country’, Shirin Ebadi, an Iranian political activist, lawyer, former judge and founder of Defender of Human Rights Center in Iran, explains her politico-religious views on Islam, democracy and gender equality. She writes: “In the last 23 years, from the day I was stripped of my judgeship to the years of doing battle in the revolutionary courts of Tehran, I had repeated one refrain: an interpretation of Islam that is in harmony with equality and democracy is an authentic expression of faith. It is not religion that binds women, but the selective dictates of those who wish them cloistered.”

Ebadi was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize on 10 October 2003 for her pioneering work on democracy and human rights, especially those of children, women ad refugees.

The Hijab Row

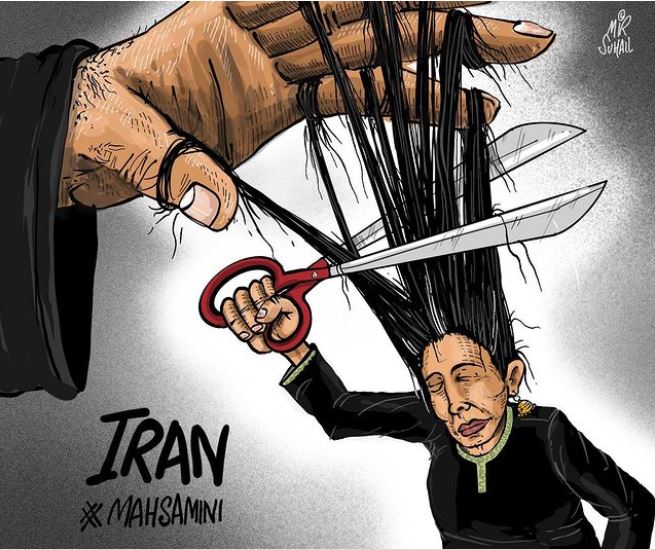

Let us revisit the tragic story of Mahsa Amini, a 22-year old Kurdish-Iranian woman who died in custody on September 16, 2022, three days after being arrested by the so-called morality police for allegedly violating the country’s policy on women’s dress code. While the Iranian authorities claim the death was natural, her family denies official reports, alleging that Amini was beaten to death.

The incident triggered a series of anti-establishment protests which spread across many Iranian cities. Expatriate Iranian communities, journalists and celebrities around the world rallied in solidarity in many countries, including Turkey, Canada, United States and United Kingdom. Social media is trending with videos where women are defiantly cutting their hair and burning their headscarves in public to the cheers and chants of zan, zindagi, azadi – women, life, freedom – and marg bar diktatur – death to the dictator. Hashtags for #mahsaamini trended the internet.

Dismayed at what it called “interference and hostile media coverage of the nationwide unrest” triggered by the death of Mahsa Amini, Iran summoned the British and Norwegian ambassadors, and criticized the U.S. support for the “rioters” – a label Tehran often uses for protesters – amid security crackdown and curbs on internet and other modes of communication. As of October 2, over 76 people had reportedly lost their lives and many more arrested in the stringent police action to crush the protests.

The History of Hijab

For a long time, hijab has been a topic of debate within and outside the Muslim world. In Islamic countries where Shariah is enforced, such as Iran and Afghanishtan, women are required to follow a strict dress code. There are also many countries where millions of Muslim women are not obliged to follow the Shariah dictates, yet many of them are forced into a strict dress code owing to social compulsions. Many women, however, do tend to wear a certain type of outfit as a matter of personal choice. Here, it is important to distinguish between cultural practices and the tenets of Islam, which are not strictly defined anywhere. Often, the distinction between the tenets of Islam and cultural practices is lost in the hotchpotch of ignorance and misinformation.

Historically speaking, a headgear – whether a scarf, a turban, a cap or a hat–was simply a protection against extreme temperatures, viz., heat, cold, or other climate changes. It was used both by men and women. In many old cultures, however, the head was also considered to be the most important and, perhaps, sacred part of the body. Headgear was also a mark of one’s social status, an indication of a privileged social background. Often adorned with decorative trinkets, a headgear in such a situation has little to do with the concept of morality and more with superiority. Im many societies, pulling a headgear off could be the most disdainful act one could commit against someone they hate.

The concept of a face veil, such as naqab in the Middle East or ghoonghat in the Indian context, as also observed in the conservative western societies of yore where women would draw a net under a hat over their face, could be viewed as an extension of the headgear. In extreme cases, women of upper classes would travel in palanquins carried on their shoulders by lower class men. In a socio-cultural context, such a covering is an extreme form of protection of the perceived sacredness of a woman of higher social status where the rest of the world is barred from even looking at her. In a religious context, it is as an extreme form of protection of morality where a woman must completely conceal herself lest she attracts sexual attention. Thus, whereas man is some sort of a powerless character absolved of being in charge of his own chastity, a woman is entitled with an extraordinary power to seduce or corrupt a man, and must, therefore, be disempowered.

The Way Forward

Recall that many Iranian journalists and human rights activists continue to be behind the bars for their progressive, anti-establishment views. People in Iran are often penalized for protesting against political and social repression and the country’s deteriorating state of economy. While the fight for human rights must continue, any foreign interference in Iran’s internal affairs is vehemently opposed by nationalist Iranians irrespective of their ideologies. Foreign interventions, which include calls for additional sanctions, isolation and regime change, are not only unnecessary, such knee-jerk responses are likely to be counterproductive. The ongoing protests in Iran are part of a larger movement which indicates a growing demand for promoting and expanding women’s rights in the country. There is an increasing need for a sustained dialogue between people of various ideologies, a serious discussion to revisit the issue of women’s rights not only in Iran but also in several other countries where women and other marginalized groups face varying degrees and types of discrimination and injustice. It won’t be out of place to conclude with a quote from Ebadi’s book: “…..change in Iran must come peacefully and from within.”

Dr. Sadaf Munshi is a US–based linguist, writer, critic and visual artist of Kashmiri origin.