The book begins with the experiences of the author as an entitled American who sets out to find answers to questions in the wake of 9/11 and ends with his understanding, through his stay in Kashmir and Turkey, of the predicament of the persecuted peoples.

Jaspreet Kaur

January of 2019 was my first visit to Kashmir. While I was soaking in the wintry black, white and grey, with the occasional day of bright blue sky when the sun shone at its brightest, what struck me were the heavily armed men in uniform dotting the entire landscape. I have since referred to them as G.I Joes, reminding me of the action figures which we would place around the house as kids.

Little did I know at the time that these action figures of the ‘real American Hero’ would actually point to the role of that all-powerful country in the politics of the region.

During my week-long stay, I met and spoke to many people. Almost all had stories to relate – some directly affected and some who have known of relatives, friends, neighbours affected physically, emotionally and mentally by the conflict. These are the common people who are caught in the crossfire of the Public Safety Act, the Armed Forces Special Powers Act and now the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act; centre and state; militants and security forces. In the midst of this new normal, the common man was just trying to survive, to earn a living and look after his family. While all of us, including from across the border, debate about the territory that is Jammu and Kashmir, we have neglected and ignored the people. And certain sections of the media have overly hyped the situation and assisted in people on the mainland forming an opinion of the people of Kashmir.

Months after my visit, the Valley was filled with a sense of foreboding. Sending additional troops to the already most militarized zone in the world and the ominous evacuation of all non-locals, tourists, pilgrims, students, and labourers eventually made sense on August 5, 2019, once again pushing Kashmir and its perennial suffering on to the world stage.

My recent visit was when Srinagar hosted the G 20 summit, attended by a handful and ignored by most in Kashmir. Walking the streets of Srinagar, especially the Polo View Road, one got the same ominous sense of foreboding. The increased number of bunkers and check posts were blindfolded with Srinagar Smart City banners in the hope of blindfolding the visitors.

Curtain Raiser

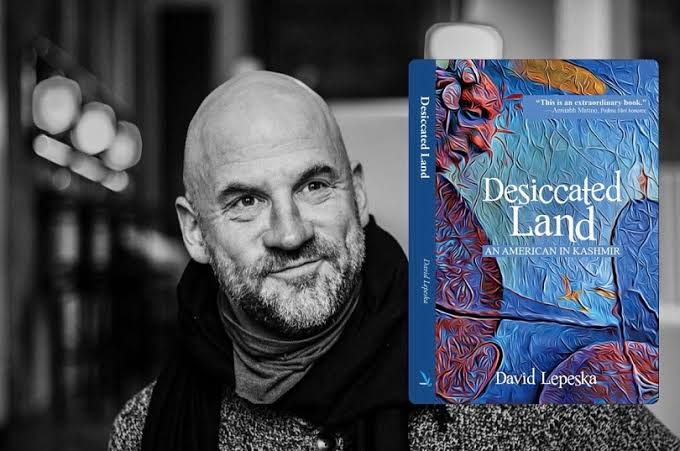

David Lepeska, with his Desiccated Land:An American in Kashmir, has attempted to lift this very blindfold for the reader.

David, an American Journalist, worked for the daily Kashmir Observer in 1998 and then later in 2006, during which time he developed a deep understanding of Kashmir, its history, culture and its people. His book is an engaging memoir of tumultuous years of Kashmir that have added successively to the ‘catalog of subjugation’ and consumed so many lives and torn so many families apart.

The book is an attempt at connecting Kashmir’s past and present and has brilliantly woven its history through the geopolitics of the present times. The author uses archives, personal interviews and books for his study which looks quite objective and unapologetic. The book traces the history of the Valley which is incomparable to any for its ‘uninterrupted history of persecution’. It’s the “Cauchemar,” as nicknamed by Agha Shahid Ali.

The book presents an excellent understanding of not only the politics of Kashmir vis-a-vis the Indian government centred at Delhi, but also its place in the geopolitics of the region which has defined Kashmir’s modern history, post 1947, beginning with the ‘British Empire’s bloodiest failure’. Through historians, writers, politicians, separatists, journalists and the common man, the book presents Kashmir in a way that only a person, a traveller, a visitor, intent on learning about the ways of the place can. The author’s motive, as a ‘qualified upper-middle class’ American is to understand the ‘Muslim World’ post 9/11.

Multiple Factors at Play

His journey begins as an ‘entitled’ person from a country that prides itself on its ‘exceptionalism’, which the author, rather humorously, with an understanding of myths and history, compares to the Satisar – both ‘dry as two-month old naan’. The idea of the false paradise, encapsulated in Frank Capra’s It’s a Wonderful Life, begins with his own family.

The decline of America’s exceptionalism that which made it interfere in orders of other nations has seen the rise of the far right and populism, as in Turkey, Brazil and India.

The author highlights the role played by the CIA, and various US presidents, including the Nobel Peace Laureate, Obama, in referring to the Kashmiri militants as terrorists when talking to Delhi and as freedom fighters when talking to Pakistan. Added to this has been the Indian government’s role in the rigging of the elections in the Valley.

The book presents the ideas and characterisations that have become the enduring symbols of the mainstream Indian discourse, that is, people crazed into fanaticism by their religious beliefs, militancy as unprovoked aggression against the state, good Kashmiris who are naturally Indian versus bad Kashmiris who buy into Pakistani propaganda. The media narrative has diminished the difference of terms such ‘terrorists’, ‘extremists’, ‘separatists’ and ‘militants’, by interchanging these at will.

The onset of the insurgency and rise of the local outfits, along with the other political players and layers of agencies, has threatened to destroy the very fabric of Kashmir built on Kashmiriyat. David Lepeska understands Kashmiriyat or the ‘united bherunda’ as an emotion, that has been politicized and the meaning mutilated. The now mythic Kashmiriyat, the syncretic blend of Shaivism and Sufism that came to Kashmir through preaching and not the sword is being threatened by the ‘blurred’ Islam and Hindu fundamentalism. The ‘uniquely tolerant strain of Islam’ developed in the Valley through the teachings of the Persian Sufi Mir Sayyid Ali Hamdani, Hindu sage Lal Ded and her Muslim disciple Nund Rishi.

While Kashmiris fight for their autonomy, which seemed to align with ‘Bush’s call for global freedom’, the rest of India under the present dispensation has been ‘Kashmirized’. David laments that in the future we might see the ‘Kashmirization’ of any nation that strives for autonomy or independence.

A Traumatized People

Politicians, lawyers, civil society leaders, activists and even journalists doing their jobs have been subjected to indiscriminate incarcerations, and muzzled, and many shifted to hostile prisons outside the state. The administration’s bid to peddle normalcy, while it remains an “information black hole,” by attracting the tourist population to the paradise is unjust and exploitation of the suppressed people. The locals are now weary and exhausted to the extent that, as the author describes, a gathering for any happening, which to most anywhere else would appear unusual, is no more tense than a ‘bridal wazwan’.

This game of normalcy falls flat given the rising cases in hospitals. The book has a large section devoted to the ramifications of the conflict and how the lives of people have been destroyed by a relentless spiral of violence. The much ignored mental health issues due to post-traumatic stress disorders, which have risen exponentially, have been consistently ignored by those who govern. Drug abuse and domestic violence are on the rise.

David presents a pretty balanced overview of the history and the present status of the Kashmiri Pandits. The migration from Kashmir and its causes has always been a contentious debate. The migration had many factors and could have been avoided but for the failure of the successive Indian governments in dealing with the Kashmir issue. The Pandits, in addition to their pride and obstinacy, too have been the victims of a larger political game.

The book has a wonderful unapologetic essay on the evolution and the closure of cinema in Kashmir. It also discusses the Hindi film industry’s cinematic representation of Kashmir and the loss of interest in theatre, dance, music, reading, neglected libraries and museums, and several other cultural aspects due to years of conflict and enforced social norms. There has been a brain-drain as those who wish to learn seek opportunities elsewhere. Little is being done to provide even good primary education, employment or improve infrastructure, especially in the rural areas.

The book extensively covers, through the author’s own experiences, the hurdles and anguish of long and regular internet shutdowns, power cuts during the bone-chilling Kashmir winter, when the only saviour still is the pheran and the kangri.

The author acknowledges, understands and is able to state what each actor in the saga of Kashmir should have or needs to do. The book begins with the experiences of the author as an entitled American who sets out to find answers to questions in the wake of 9/11 and ends with his understanding, through his stay in Kashmir and Turkey, of the predicament of the persecuted peoples—be it the Kashmiris, the Kurds or the Black Americans.

Jaspreet Kaur is a Delhi-based architect, urban designer, Trustee Lymewoods & Span Foundation and Consulting Editor of Kashmir Newsline.