The spymaster is widely seen as an authority on Kashmir and someone not in favour of a muscular policy while dealing with Kashmiris.

Shome Basu

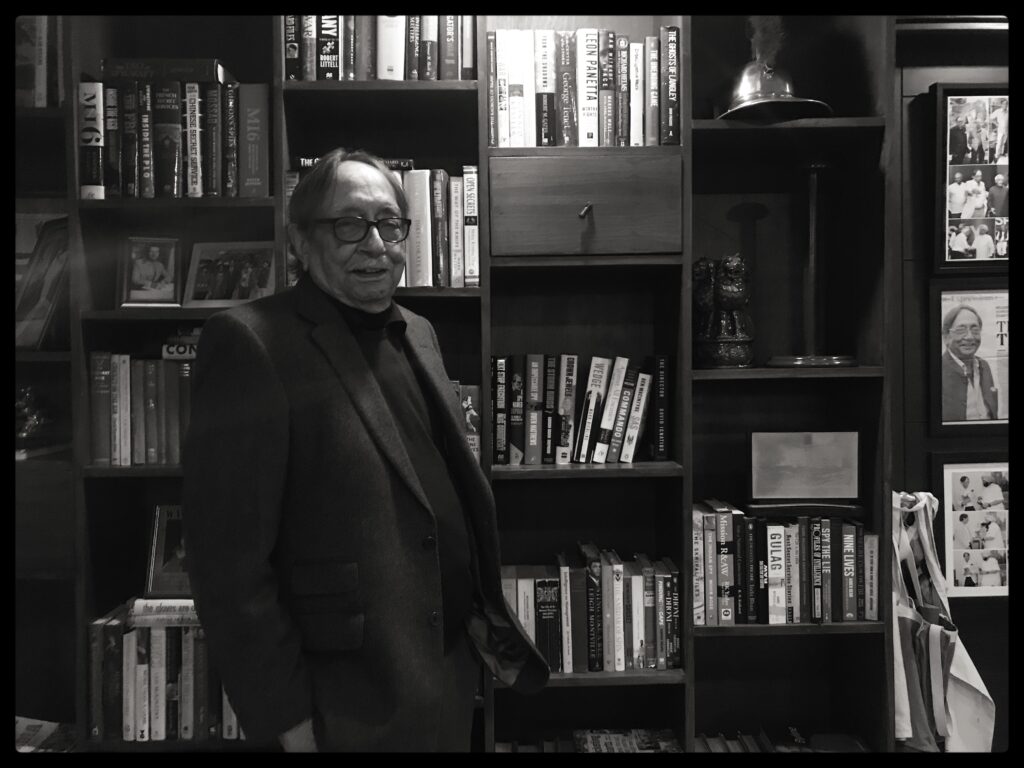

On a chilly January evening, over cups of Kashmiri kehwa, Amarjeet Singh Dulat, the former IB and R&AW chief, is engrossingly speaking about Kashmir – a dystopian but stunningly beautiful Himalayan valley which has shaped his life.We’re sitting in a neatly arranged study in the basement of his New Delhi home. A collection of spy fiction by John le Carre and Ian Fleming and other hardcovers on geopolitics, history and cricket are stacked on the varnished racks with Ashoka Stambh, India’s national emblem, and a gallery of awards to go with it.

Kashmir

Kashmir is a difficult, yet endearing, place which leaves its imprints on the lives of the people associated with it. Dulat, like many others who have lived their lives or parts of their lives amidst Kashmir’s deceitful beauty, seems possessed by it.

The superspy definitely knows more than he speaks or writes about Kashmir. As the station head of the Intelligence Bureau (IB) in Kashmir in the early 90s, Dulat was a key player. Even during his role as the head of India’s external intelligence agency, R&AW, he played different roles in the Kashmir story.

Now an octogenarian, Dulat is still active and alert. The three books authored by him—including the one he co-authored with former ISI Chief General Asad Durani—have revealed many failures and also the achievements of India’s intelligence agencies. The latest of the three books – A Life in The Shadows – is a memoir.

Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy

In 1987, Dulat got a call from his boss at the North Block, where the Home Ministry offices are located, to go to Kashmir. He was stationed in Bhopal. Dulat was hesitant at first due to his bronchial issues. He was worried that Kashmir’s cold weather might be difficult for him to face. His boss, M K Narayanan, however, managed to prevail. So Dulat moved to Kashmir and, ever since, the two are intertwined.

As he speaks of his assignments and operations in Kashmir, he has a chapter inspired straight from John le Carre’s ‘Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy’.

Paris 2000. A gentleman comes in a red Volkswagen Passat to meet him at a café`. The man looks around, walks over and extends his right hand: “I am Hashim Qureshi.”

To which he responds: “Mujhe Dulat kehte hain – my name is Dulat.”

Here was one of India’s senior spies meeting a man who was to open up on Kashmir and the militancy besetting it.

Qureshi had driven all the way from Amsterdam.

“I heard about Hashim Qureshi in 1989, when I was first posted to Kashmir and the region was beginning to erupt into a full-blown insurgency,” recalls Dulat. On 30 January 1971, Qureshi, along with his cousin, had hijacked an Indian Airlines aircraft—a Fokker F27 named Ganga—that was en route to Jammu from Srinagar and had taken it to Lahore. That was the time India was training the Mukti Bahini in East Pakistan. Pakistan had suspected that the hijacking was India’s ploy to find an excuse to cut off the air connectivity between the eastern and western wings of Pakistan.

Qureshi, in that meeting with Dulat, candidly admitted that he had been on the payroll of the Border Security Force (BSF). Back in 1989, Dulat had come across an opinion piece in a Kashmiri newspaper in which Qureshi had written against militancy. It was the time when insurgency had overwhelmed Kashmir. After reading the article, Dulat had seen hope in him.

Dulat was put across to Qureshi by the former chief minister of J&K, Dr Farooq Abdullah. The relationship grew and they started trusting each other. Qureshi wanted to come back to Kashmir but he had cases against him. Dulat found him reasonable and someone who could help in scaling down the levels of violence.

Dulat got in touch with the then IB Chief, Ajit Doval. Doval spoke to Qureshi. After the meeting, Doval called Dulat and said: “Sir, ye to kaam ka aadmi hai – he is a useful guy.”

When Qureshi crossed the immigration at New Delhi’s IGI airport, J&K Police, along with the IB, was waiting for him outside the green channel. He was taken into custody and put on a two-week remand. He was questioned and then transferred to a jail in Jammu. Qureshi was subsequently released and given various assignments. He now lives in Kashmir under security, having gone into retirement after working actively over the last couple of decades under New Delhi’s patronage.

Kashmiriyat

Vijay Dhar, a Pandit businessman from the valley, set up a branch of the prestigious Delhi Public School on the outskirts of Srinagar in the early 2000s. “Such measures have helped build confidence among ordinary people. Children of former militants and government servants and many security officers go to the same school and grow up together,” says Dulat.

“Other affluent Pandits could also come forward with good ideas like building hospitals. It would do a lot of good to the valley and would strengthen the bond of togetherness between the two communities,” he says.

Rubbishing the idea of ghettos for the Pandits, inspired by Israel’s settlement policy, Dulat says it won’t take Kashmir anywhere. “Kashmir can progress only if the majority Muslims and the minority Pandits live between each other. That is the real Kashmiriyat,” says Dulat.

Dulat Doctrine

In 1991, a foreigner was kidnapped in Kashmir – the first occurrence of its kind. The incident shook the world and the Kashmir conflict made it to the international headlines. Johan Jansan and Jan Ole Lowman, the two Swedish engineers, were working for the Uri Hydel Project in north Kashmir. Militant outfit Muslim Janbaaz Force (MJF) was behind the kidnapping and it took three months for the Swedes to negotiate with MJF in Pakistan to get the engineers released. Dulat, at that time, was heading the Intelligence Bureau in Kashmir.

At his office one day, Dulat got a phone call from the Army that it had caught a big fish – Firdous Sayed aka Babar Badr, the chief commander of MJF.

“While in army’s custody, Firdous was deeply impressed by the fact that he could argue and debate with the Indian Army and intelligence officers, while in Pakistan all he had to do was follow the command,” recalls Dulat. He was shifted for some time to a Jammu jail from where he was taken to New Delhi, masquerading as a Sikh to keep his real identity hidden, to meet Rajesh Pilot, who was the minister of state for Home.

“Rajesh Pilot,” says Dulat, “took keen interest in Kashmir.” It paid off and soon the entire MJF cadre surrendered which came as a big jolt to the separatist movement and the organisation’s Pakistani handlers.

“It led to more successes for us,” recounts Dulat.

In a cold February of 1996, there was a press conference held at Srinagar’s busy Ahdoos hotel by Babar Badr and three other major former militant commanders. The other three were Bilal Lodhi, Imran Rahi and Mohi-ud-din. Bilal Lodhi, a lawyer, was the chief commander of the dreaded Al Baraq that had inflicted heavy casualties on the security forces. A little more than a year ago in 1995, all four were in jail. They were now getting clicked by photographers and not hiding underground anymore. All four had been kept in custody on charges of distributing arms, planning attacks against security forces and liaising with the ISI for funds and weapons.

“At the press conference, they declared they would abjure violence and were ready to hold unconditional talks with New Delhi to find a solution to the Kashmir crisis,” says Dulat.

“ISI,” says Dulat, “was more interested in these men carrying out wider terror activities against India rather than remaining confined to the Kashmir movement.”

IB under Dulat believed in co-opting the militant leadership as the first option rather than using an out-and-out muscular policy. It came to be known as the Dulat Doctrine and it led to great successes.

“To bring these people and many others like them under one roof to talk peace when Pakistan was supplying them with money and arms was a major success,” says Dulat smilingly.

The Ceasefire

One of the key figures in Kashmir at the peak of militancy was the top Hizb-ul-Mujahideen commander Abdul Majid Dar. While interrogating a man in Kashmir who was in the police custody, Dulat asked him about Dar. “Who doesn’t know him?” the man responded quickly. Dulat, at that time, was heading India’s external intelligence agency, R&AW.

Dar was in-charge operations and second only to Syed Salahuddin in the Hizb hierarchy. Dar carried a greater heft as a tactician than Salahuddin who was more of an ideologue. Hailing from Sopore, Dar ran a laundry shop before joining militancy. He was based out of Pakistan from where he directed the Kashmir-based Hizb cadre.

After thoroughly interrogating the man in the police custody, Dulat latched on to something that could lead him to Dar. It was Dar’s love of life whom he had married, Dr. Shamima Badroo. It was a second marriage for both of them.

Under the very nose of ISI, R&AW convinced Dar to return to Kashmir and engage in political mediation.

Dar convinced his handler, a brigadier from ISI, that he would like to return to Kashmir. The ISI officer went and talked to Dar’s boss, Salahuddin, oblivious to the development that R&AW had roped him in.

When the proposal went to the ISI Chief, Lt. Gen. Mahmud Ahmed, he gave it a go-ahead after some deliberations. Not knowing that their blued eyed commander had shifted his loyalty, ISI also wanted to initiate negotiations. Of course, on its own terms!

Dar was sent to Kashmir with a belief that he would remain loyal to Pakistan’s cause as was the motto of his pro-Pakistan militant outfit.

Home Secretary Kamal Pandey along with some people from IB flew from New Delhi to Srinagar to meet Dar. It was August 2000. Kashmir valley was witnessing a ceasefire declared by the Hizb leadership with complete endorsement from the supremo, Syed Salahuddin. R&AW also realized that Dar was the real deal and Salahuddin a mere paper tiger. Even ISI relied more on Dar.

After somehow finding out that R&AW was behind the game, ISI felt stabbed in the back by Dar. The ceasefire was quickly called off by Hizb-ul-Mujahideen which was followed by a broad daylight assassination of Dar. Two gun-wielding youth barged into his ancestral house and fired indiscriminately, killing Dar on the spot and critically injuring his mother and sister.

Dar’s wife accused an ISI officer of vitiating the atmosphere against Dar in Pakistan that culminated in the latter’s assassination. Within days, Dar’s wife was also fired upon, which left her debilitated and wheelchair-bound for the rest of her life. It was assumed that Dar’s Divisional Commander was involved in his murder, but why would they attack his wife?

“May be they felt she was involved in bringing Dar back to India and was working for R&AW when she was in Pakistan,” concludes Dulat.

Shome Basu is a New Delhi-based senior journalist.