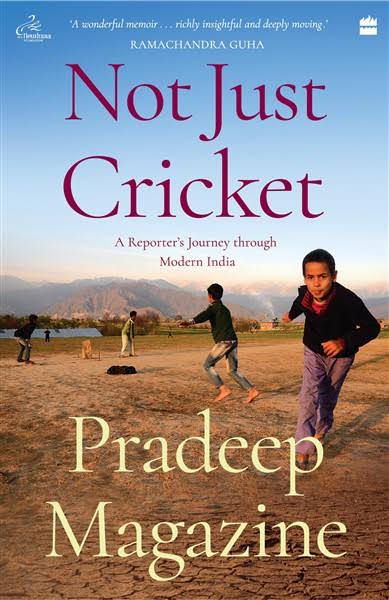

Series of excerpts from Not Just Cricket by Pradeep Magazine.

The common opinion among many elderly people was that because India is so big and powerful, it behaves like a bully. Their wish was that it should instead be like an ‘elder brother’ and take care of its weak, estranged ‘younger brother’.

Kashmir: At Home without a Home

It was around that period I started visiting Srinagar more often, finding any pretext, sporting or otherwise, to get my office to send me there for reporting. I was trying to renew my connection with my homeland to make sense of the tragic loss of my roots. My holiday visits to Kashmir had stopped after 1989 and our family home was abandoned soon after. In this attempt to reconnect with the land of my birth, I was neither bitter nor thirsting for revenge. The same could not be said for many of my relatives, some of whom had left the Valley in the dead of night, fearing for their lives. They had seen several among their community, even their own relatives, killed; when a call for Azadi was made from the loudspeakers of the mosques, a wave of terror would sweep over the Hindus. I heard many stories of Muslim neighbours urging Hindu residents to not leave, though the terror of the militants was such that they could not assure their safety either. In many cases, fleeing Hindus had left their house keys with their neighbours, who had assured them that they would watch over anything left behind. For every story of a hostile neighbourhood there were multiple accounts of friendship and support. It was the killings by the militants that forced the Hindu Kashmiris to flee their homes. What I find interesting is that younger people seem to have more hatred against the Muslims. There is a strong belief among them that Kashmiri Pandits were butchered on the streets of Srinagar and the locals had joined in these attacks. It is not that older people have a lot of sympathy for Kashmiri Muslims or that they do not blame them for forcing them out, but their level of hatred is far lower. Given a chance they would still want to return to Kashmir and try to recreate the old world where they lived happily side-by side with Muslims even if they were the ‘other’. My own early childhood impressions from the late fifties and early sixties are more of friendly individual interactions with an underlying tension between the two communities. During peaceful times, Pandits too saw India as an alien land where the more adventurous would aspire to go for better economic opportunities. Only at the time of crisis did India become a protector that could save us from annihilation. In 1989, Mufti Mohammad Sayeed of Kashmir had been just sworn in as the country’s first Muslim home minister when his daughter Rubaiya was kidnapped by militants. The Indian government released arrested militants in return for her release. Kashmir erupted and thousands poured onto the streets shouting Azadi slogans. M. Ishaq Khan, a professor at Kashmir University, had written a book called Kashmir’s Transition to Islam, published in 2002. In the book, he concludes that the majority of Hindus who converted to Islam did so under the influence of Sufism, which had taken root in the eighth century and spread throughout Kashmir by the fourteenth century. Khan argues that the lure of equality for all, regardless of caste or religion, is what attracted the majority of lower-caste Hindus in Kashmir to Islam. He also acknowledges the coercive and even brutal role played by Sultan Sikandar Shah Miri, known as Butshikan (idol-breaker), in the late fourteenth to early fifteenth century in converting Hindus to Islam, but not to the extent that is widely believed and documented. Khan’s book presents a more benign face of Muslim influence in Kashmir, represented through the Sufi saints whose call for justice, equality and love attracted many Kashmiris. Though no one denies the role these saints played in spreading Islam in Kashmir (and also in the rest of India), many contest the claims that they played a greater role than the sword and brute force in mass Hindu conversions. I am not a historian, but what had always fascinated me was the fact that Kashmiri Hindus in the Valley comprised only Brahmin Pandits. I remember being told at home and outside that we are the only community in India which does not believe in the caste system and that is the reason why there are no lower castes in our small community, an assertion that glossed over the fact that all the lower castes had converted to Islam. I was to become aware much later in life that during Ashoka’s time, Kashmir was almost entirely a Buddhist land. How Hinduism and later Islam literally purged the Valley of Buddhism was not the subject of popular folklore in our homes in Kashmir. Instead, we heard the tales of the reign of terror unleashed by Miri as he forcibly converted Hindus to Islam. We were often told that during those terrible days only a few Brahmin families had refused to convert, and all the surviving Hindus in Kashmir were their progeny. In the oral narration of our history, the lower castes did not exist. Among the historical examples given by Khan is a revered Sufi saint of Kashmir called Nund Rishi, also known as Sheikh Nur-uddin Wali. Nund Rishi was a follower of another revered Sufi saint of Kashmir by the name of Lal Ded, a Shaivite mystic saint whose vakh (verses) were part of everyday life discourse at our homes when I was a child. Poet Ranjit Hoskote, in the introduction to his translation of Lal Ded’s poems in exquisite, simple English prose, I, Lalla, writes: ‘Vitally, given that Kashmir is now almost completely Muslim region, it is instructive to recall that Lalla is regarded as a foundational figure by the Rishi order of Kashmiri Sufism, which was initiated by Nund Rishi or Sheikh Nur-ud-din Wali (1379–1442), seen by many as her spiritual son and heir.’ Lal Ded was also revered by Muslims, while Hindus claim Nund Rishi as one of their own. Nund Rishi’s tomb is at the famous shrine of Charar-e-Sharif. In 1989, when Kashmiris realized that Azadi could be a reality, they came out on the streets in thousands and planned a march to the Charar-e-Sharif Dargah to thank their patron saint for granting ‘deliverance’ from Indian rule. The shrine was razed to the ground in 1995 during a gun battle between Indian security forces and militants who had taken shelter there. It was rebuilt later and I visited the shrine on my trip to Srinagar in 2004. On that trip I also made an appointment with the professor and met him at his home. I still remember I was nervous as this was only my second visit to a Kashmiri Muslim family. The first had been with my brother and mother to a well-known Muslim business family of Srinagar in the seventies. In the typical Kashmiri tradition of hospitality, they had served us kebabs, which my mother was reluctant to eat, fearing they would be made of beef. After much persuasion and assurance that it was not beef, she did eat them, though I am not sure that she was convinced. It was not that she thought her hosts were lying, but her mind had been conditioned to believe that any meat that Muslims cooked had to be beef. Khan’s welcoming smile, and the Kashmiri kahwa and takhtech (tea and sweet bread) he served, put me at ease. In his narration of events, it became clear that the brutal phase of militancy of the early nineties had been terrible for all Kashmiris. He said that the militants started killing anyone who did not cave in to their demands, which was not the Azadi people had hoped for. ‘Most of them came from the lower strata, Wattals and Jamadars (scavengers) and they [the militants] would demand money, even women, from the locals,’ said the professor, ‘and that turned people against them.’ Khan also felt that the exodus of the Pandit community—which was the backbone of bureaucracy, banking and education in the state—led to a collapse of administration and created a lot of problems for the people. According to him, these were some of the factors that made militancy and the gun culture unacceptable to the common Kashmiri. They were the sufferers now and hankered for respite, which was a reason for the relative peace prevailing at that time in the Valley. Khan told me that there had been a time in the nineties when hardly any shop would open, the streets would be deserted and no one would dare venture out after 4 p.m. Fear, whether of security forces or militants, had turned Srinagar into a ghost town. A cousin of mine, Vijay Bakaya, had served as the principal secretary to the chief minister of Kashmir and later become the chief secretary of the state. He was the divisional commissioner at the time of the mass migration of Kashmiri Pandits from the Valley, and responsible for all the arrangements made in Jammu for the fleeing migrants. Being a Kashmiri Pandit himself, Bakaya was the link between the Pandits and the controversial J&K governor Jagmohan at the time when Pandits were being targeted by militants.

Excerpted with permission from Harper Collins.