The sufi songstress will always be remembered for her unforgettable folk songs.

Lily Swarn

Whenever the strains of Reshma ‘s arresting, unabashed voice cut through the borders and reached people’s hearts, no one could help being moved by its pure passion. It was as if the desert sands had shifted around us when her haunting voice came with its rustic richness of timbre which was embossed with raw emotion. Generations of her banjara tribesmen forefathers must have crooned in the same manner as they crossed the silent desert. Known as Bulbul-e-Sehra–Nightingale of the Desert–Reshma was born in 1947 in a gypsy household of Loha, Rajasthan in India.

Her mother started calling her Reshma, the silken one, and soon her siblings followed suit. The family moved to Karachi when she was a babe in arms. Her father, Haji Muhammad Mushtaq from Malachi, Iran was from a tribe that had converted to Islam. He was a horse, camel and cattle trader so they had to move from place to place. Reshma reminisced that they would often pass through fairs and village marketplaces ; she called them mele te mandiaan where she heard sweet voices singing and performing on the stage. The desire to sing like them had taken birth early in life.

Reshma had once gone to Shahbaz Qalander’s mazaar to ask for the boon of her brother’s wedding. All of 12 years, she was singing seeped in devotion and supplication. She gave the beat with a gadvi – a pitcher. Saleem Geelani, a producer from Radio Pakistan, heard her and was instantly smitten by her unique and captivating voice. In Reshma’s words, “some babus were also standing there. They approached me and asked my name.”

Geelani asked her if she would sing for the radio. I don’t know, she replied. He gave her his card and told her to meet him.

Their caravan reached Karachi after two years. Reshma fished the card out and went to meet him with her family .The doorkeeper wouldn’t let them in as he couldn’t believe that the acclaimed TV and radio producer would want to meet a bunch of nomads. He scoffed at them. The family somehow managed to convince the gatekeeper. Sarvat Ali Khan, the producer at the radio station recalled the incident thus: “She refused to enter the studio thinking a man was standing inside. It was a pillar-like structure that was actually the microphone.”

Reshma was used to singing unbridled in the vast expanse of sands, sitting astride a camel that swayed with a leisurely gait. History was made that day in 1968. Her recordings were received with unprecedented appreciation but the gypsy had gone into hiding. She couldn’t be traced. The masses made lal meri a massive hit. Pirated tapes reached India and Reshma was an overnight phenomenon. Her unconventionally husky voice singing about the Sufi mystic in spiritual bliss was so different from what was earlier heard over the air waves. Her picture was published in the newspapers with a reward of 2000 rupees for any information about her.

Reshma revealed during her interview for Lok Virsa that since she was completely illiterate, the recording studios had to make her memorise the lines of the songs. Sometimes it took almost 15 days to learn by rote. She bought herself an Urdu alphabet booklet and learnt to sign her name. She smilingly told the audience that recognising words became slightly easier after that. Television was another challenge. She was accompanied by her sister for the first recording in a studio. Never having experienced this earlier, she shyly confessed that she was wonderstruck by the sight of her image in what she called a dabba – box. She was befuddled as to how she could be standing in one place and singing and also be inside the dabba at the same time!

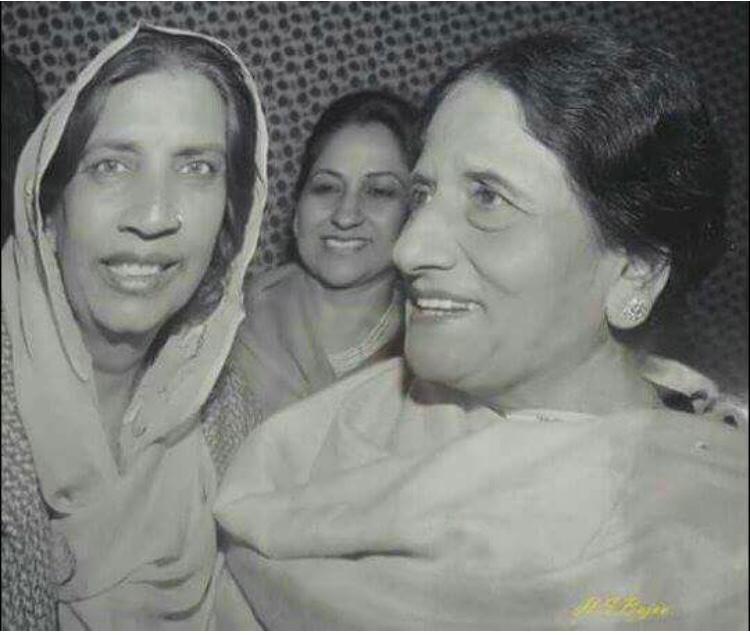

A lot of Reshma’s charm besides the glorious resonance emanating from her throat was her endearing naïveté. She remained true to her roots and always wore the traditional attire of a salwar kameez with her head demurely covered. Even fame did not rob her of her modesty. She would sing without looking up much and avoided any sort of histrionics. Earlier she also wore a thicker Rajasthani chadar to cover herself. Her dangling jhumkas added traditional glamour.

I remember her narrating an amusing incident in an interview. Though her mother tongue was Rajasthani, she got to sing a lot of Punjabi songs.

Soon she was being urged to sing Urdu ghazals and film songs. Now this was a problem as she found many Urdu words tough to learn up and understand. There was one nazm in which one of the words was shagufta. Reshma narrated with disarming candour that she would always stutter and fumble on that particular word even though the meaning was explained to her to make it easier to recollect. But this was not the last of her woes. The television producer convinced her to drape a sari even though she said she hadn’t ever tied it. He thought it would be the right attire for an Urdu nazm . A girl was arranged to help her dress up. It was with a mischievous glint in her large tawny eyes that Reshma told the interviewer that she was told to change her position numerous times while singing to face multiple cameras – sitting in the antara, then walking in the first stanza, standing in the other one and so on . She had the audience in splits as she spoke about her utter discomfiture in that recording. It seems as soon as she pronounced shaghufta correctly, so elated was she that she got up in sheer excitement and almost tripped on the pallu, the loose end of her sari.

She also innocently recounted that during her tour to Toronto, she confidently kept answering all queries in English with a crisp ‘yes’ resulting in many a comic faux pas. Reshma set up a gurgle of amusement as the audience heard her talk about Toronto as a gaon – village. She had no clue about what was being asked of her. When the Pakistani ambassador’s wife asked her why she was doing so, she quipped that she didn’t want them to know that she couldn’t understand a word.

Reshma also spoke about her soft corner for all Sikhs as they reminded her of her father who also wore a turban. Whenever there were Sikhs in the audience, she narrated this real life story of her visit to Moscow. She came out of her hotel for a stroll and got completely lost after drifting off. Gripped with fear as she didn’t follow or speak Russian language, she breathed a sigh of relief as she miraculously caught sight of a Sikh gentleman who was the owner of a watch shop. They conversed in Punjabi much to her glee. The senior gent addressed her as puttar, meaning child, which immediately put her at ease. He found the name of the hotel from the room key and safely walked the legendary singer back to her hotel.

The naturally morose vibe in Reshma’s vocals made a song sublime and raised it to another level.

She sang the epic lambi judaai for the Hindi film Hero in 1983.It was one of her hugely popular songs and she told Subhash ji that she was asked to sing this the most number of times. It is believed that thespian Dilip Kumar convinced her to sing for Hindi films. Later, Subhash Ghai the film director said: “Her singing was so powerful that her words resounded without the microphone.”

In India, she also sang in some private gatherings, prominently at actor and filmmaker Raj Kapoor’s house where Ghai heard her for the first time and asked her to sing in Hero. Raj Kapoor had earlier made Lata sing a Hindi version of Reshma’s famous song akhiyan nu rehne de as akhiyon ko rehne do akhiyon ke aas paas for his film Bobby in 1973. In 2004, Reshma recorded the song ashiqan di gali vich for the Bollywood movie Woh Tere Namm Tha.

Reshma lived all her life in Gadvi Mohalla, ShahDara, Lahore . She preferred cooking food for the family herself. Some find it strange that she was a vegetarian. It is said she had even given a name to each of her own utensils. Her favourite food was makki di roti and sarson da saag.

The nightingale passed away aged 66 after a prolonged battle with throat cancer. She didn’t stop singing till much later despite her tongue slurring. Since she couldn’t eat enough, her body had grown frail. Pan, gutka and supari played havoc with her health. She had a loyal fan following. Shaukat Ali, the famous folk singer, said on the phone after her demise: “Reshma was a magician who could kill with her voice. She was the first lady of Pakistani folk music.”

Pervez Musharraf helped her with a grant of one million rupees toward her hospital bills and ten thousand rupees a month. Though later people said it wasn’t an amount worthy of an artiste of her caliber.

“Singers of that level and magnitude are an institution in themselves and her passing away means a complete era has passed away. It is a huge loss,” Taimur Rahman, lead singer of Pakistani band Laal, said.

The lady with awards and recognitions like Sitara-e-Imtiaz and Pride of Performance liked listening to songs like rasik balma and the qawwali dama dum mast qalandar. She liked songs composed by Naushad and was a great admirer of Mohammad Rafi and Lata Mangeshkar. Indira Gandhi had invited her to meet her and she would come over often to perform in the land of her birth when exchange of artistes was allowed freely. She is reported to have said: “The borders do not matter to me because an artist belongs to all.”

She was the inaugural passenger on the Lahore – Amritsar bus as part of the peace process.

sun charkhe di mithhi mithhi kook

ve mahiya mainu yaad aanvada

(I yearn for my love when I hear the sweet sounds of the spinning wheel)

These achingly sung words will always reverberate in the firmament for music lovers like me who were spellbound by the dynamic, folksy voice and personality of this unparalleled sufi and folk artiste. Rest in eternal peace, Bulbul-e-Sehra!

Lily Swarn is an internationally acclaimed, award-winning poet and author.