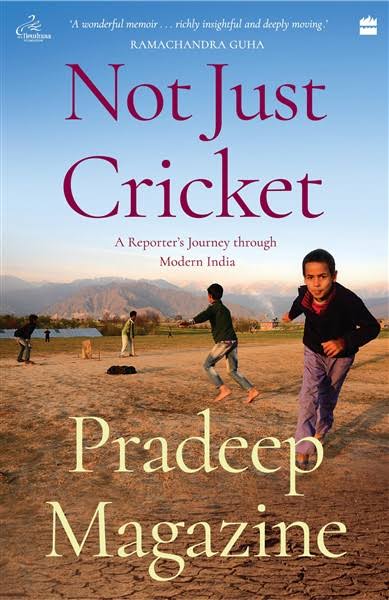

Series of excerpts from Not Just Cricket by Pradeep Magazine.

In Pakistan, while Indian journalists who were Hindu were treated with tremendous love and warmth, I found there was an underlying tension, never overtly stated but simmering below the surface, whenever Indian Muslim journalists talked politics with their Pakistan counterparts. A senior journalist by the name of Javed Ansari—who was covering that tour for India Today—had throughout the tour flaunted his Indianness with pride. I had to stop him once from getting into a lengthy, combative argument with a Pakistani journalist who was seeking a larger Muslim affinity with him. In strong words, Javed declared that he did not wish to be treated as anything other than an Indian, as he strongly believed the very idea of a nation based on religion was a flawed one. I could sense a degree of discomfort and resentment among Pakistanis to see him so obviously proud of his Indian nationality. As happy Muslim citizens of a country where the majority of the population was Hindu, he was, in Pakistani eyes, a negation of the very idea of Pakistan—a country created on the basis of religious majoritarianism.

When Citizens Become Hosts

In February 1999, the Indian Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee rode his peace bus to Lahore for a summit meeting with his Pakistani counterpart, Nawaz Sharif. On the bus were iconic Bollywood film personalities such as Dev Anand and Javed Akhtar, and Kapil Dev also found a seat. But this peace mission was followed within a few months by the Kargil skirmish, underlying the extremely fickle nature of the India–Pakistan relationship. Five years later, the Vajpayee government was about to compete in the national elections hoping to be re-elected to another term. The Prime Minister, despite opposition from his deputy Advani, wished to reach out again to Pakistan. He was very keen that the Indian cricket team should visit the neighbours again for a full-fledged cricket tour. A series dubbed the ‘Friendship Tour’ was hastily arranged with government backing. There was a lot of pre-tour hype that this was not just about cricket, but also about ‘peace and love’.

Pakistan had made unprecedented security arrangements and, in what many considered a risky step, it was decided not to have separate enclosures for the thousands of spectators coming from India. The tickets could be bought on a website, and one could choose one’s own seats. This was in contrast to previous India– Pakistan matches, where the respective supporter groups were made to sit in separate enclosures for reasons of security and crowd control. It was only later that I realized that this non-segregation policy helped in building people-to-people relationships between the two nations. I was not covering the tour as a journalist. Rather, I was keen to visit Lahore and watch cricket without the burden of writing reports and meeting deadlines. I bought tickets for myself, my wife, our eighteen-year-old daughter and a friend T.R. Ramakrishnan, who was a former fellow at The Indian Express. This time around my place of birth was a non-issue with the Pakistani high commission and getting the visa was a breeze. So it was in April 2004 that the four of us boarded the bus to Lahore for a week-long trip that held exciting prospects away from cricket, which was just a ruse to visit Pakistan. We found that most of our fellow passengers were on their first visit to Pakistan, and like us, cricket was not the priority or the main reason for their visit. In a journey that lasted almost twelve hours, we became acquainted with several of our fellow passengers, most of whom had roots in Pakistan. Many of them had addresses of their ancestral houses in and around Lahore, from their parents or grandparents who had fled in the bloodbath of Partition. Some of them had only a vague idea of the place they would have to search for, based on the description they remembered their parents giving them. My father had been posted as a customs official at Attari near the Pakistan border, and thus I was familiar with the region. When we passed the border, it did not seem like we had entered a different country, as everything appeared just the same: the land, the trees, the smells and the landscape, typical countryside in Punjab. Yet something had changed. All of a sudden, a vociferous, passionate cry went up from the majority of the passengers: ‘Jai kara Sherawali da’ (victory to the one who is mistress of the lion she sits on) that was followed by: ‘Bol Sanchi darbar ki jai (victory to the one who provides justice to all in her court)’. This is a very popular chant recited at temples in north India in praise of the goddess Durga, who is mostly portrayed as a female figure astride a lion. Other slogans such as ‘Bharat Mata ki jai (Victory to mother India)’ too filled the bus, and to me they seemed like war cries. The descendants of refugees of the tragic Partition were announcing their return to their homeland, which they were now visiting as outsiders. My xenophobic friend from Chandigarh, Jatinder, had also come to Lahore to try and find his ancestral home in Laxmi Nagar. He had memorized the location of the place from what his father had told him, and was surprised that the names of the streets and the locality remained unchanged despite most of them being Hindu in origin. At the house, he was moved when the present occupants welcomed him in and fed him a nice meal. As he described these touching moments to me later, I could sense that his ingrained animosity towards the ‘other’ had perhaps disappeared. Our hotel was next to a bustling shopping complex, and after checking in, we stepped out to see the sights of the busy market. Our curious eyes and the bindi on my wife’s forehead gave us away as Indian tourists visiting for the Test match. Reassuring smiles from strangers greeted us. Then something unexpected happened: two young women walked up to us and introduced themselves as medical students.

They expressed warm words of welcome: ‘Please feel at home. Pakistan is as much your country as it is ours, we are students and if you need anything do let us know. Enjoy your stay here and all the best.’ This spontaneous gesture of warmth from total strangers in a marketplace overwhelmed us. It set the tone of a visit that saw Pakistanis at every step going out of their way to make visiting Indians feel comfortable and welcome. It was as if the Pakistani public had taken upon themselves the responsibility of bridging the divide between them and their neighbours. Though we had visas for only Lahore, we were keen to visit the archaeological site of the Indus Valley civilization near Harappa village, a four-hour drive from Lahore.

Locals assured us that there would be no problem if we travelled out of Lahore, a risk we happily took without inviting any trouble. After moving around the ruins in Harappa, which were deserted, we walked towards the village. A young boy, barely in his teens, met us on the way and was thrilled to know we were from India. He was a fan of the Indian actor Shah Rukh Khan and had written a letter to his idol. He had a request for us: could we post that letter for him once we were back in India? He asked us to wait while he fetched the letter from his home. Not having the heart to say no, we waited until he came back with the letter, written in Urdu. The youngster also pointed out a particular row of houses and said that they had belonged to Indians, and no one lives in them anymore. We were told by other people later that it is true that in many villages in Pakistan, there are still untouched Hindu and Sikh houses, mostly in ruins now. Many of these houses are believed to be inhabited by the ghosts of those who fled or were killed during Partition, and no one dares to go anywhere near them. We decided to watch a bit of cricket as well, and sitting among the crowds at the Gaddafi stadium, we saw that there were more Indian flags than Pakistani ones that fluttered in the Lahore breeze. However, the Indian flags were not just held by Indians—even Pakistanis were holding and waving them! There was a carnival-like atmosphere in the stadium. These were unbelievable scenes, very different from what I had witnessed in 1997, when the crowds, though not hostile, had been distinctly partisan and even aggressive in their support for their own team.

Though India eventually lost the match, the crowds were still cheering and waving Indian flags, as if India had won. We were sitting next to a young Pakistani IT professional from Lahore, and he was curious to know more about India and Indians. He expressed his happiness at finally having met Indians and understanding that, contrary to what he had believed, people from the other side of the border are just like his own people and not, as he laughingly put it, ‘people with horns’. It is hard to put on paper the exhilarating emotions we experienced that day.

Excerpted with permission from Harper Collins.