With people still reeling under the impact of the 2016 demonetization, this could be yet another bolt from the blue.

Shome Basu

2016: I was in Calcutta, waiting in an ATM queue to withdraw Rs 10,000 for my mother’s medical tests. It was 7:30 in the evening when my wife called me from Delhi saying that Prime Minister Modi would be on TV in a while for some urgent announcement.

Okay, but suddenly? I got my cash, went home and turned the television on. At 8 pm came a firman that changed India forever. Demonetisation. I had only read about this in economics, but for me and other Indians, it was now real. I was squabbling with my niece, checking all the Rs 1,000 notes we had, only to find that all the money I owned was suddenly rendered valueless. For the next seven days in the city, till I boarded my flight for Delhi, I had to borrow some thousands of rupees in the denominations of Rs 100 and 50.

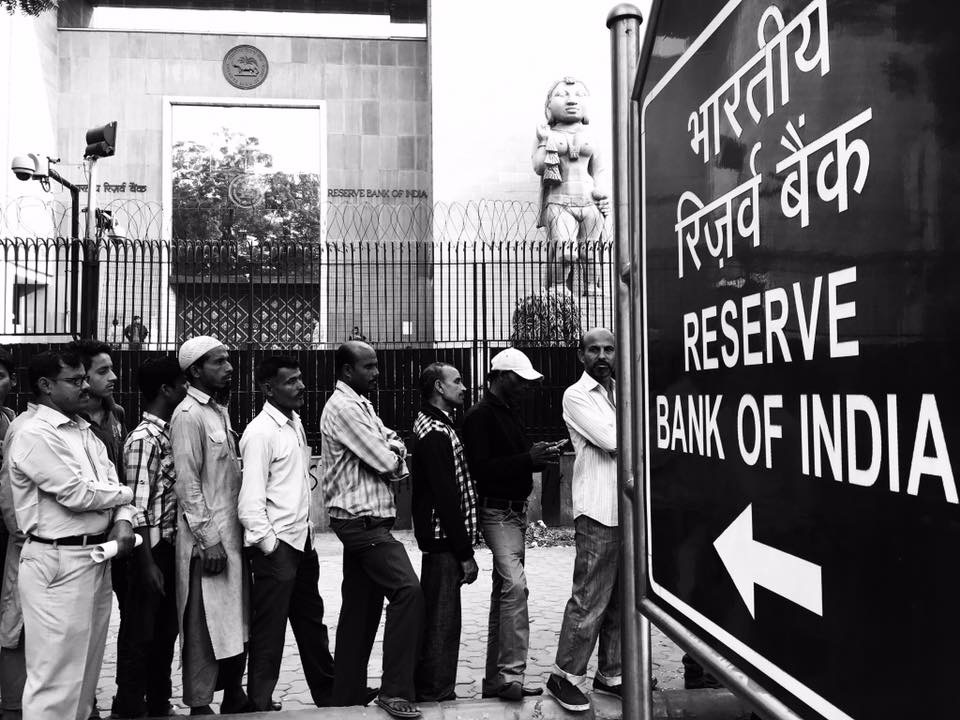

Next, I had to find out how people had been affected by this sudden edict that forced them into never-ending serpentine queues. It was reminiscent of the 1980s ration and kerosene queues. It used to take hours or even days. I never thought I would see India like that again. Everywhere I travelled, the scenes were a photocopy of the previous place. Everywhere, people had to stand in the cold winters of North India or warm days in Eastern India, waiting for currency. The myriad images that I clicked epitomize that agony.

There were cries all around. The hard-earned money of many, saved as little cash in Rs 500 and Rs 1,000 notes, was no longer of any value. It looked like Nero’s Rome. For six months, I documented the lives of people in queues. The better part of Indians is resilient – people helped each other, and the old and pregnant women were taken care of by people standing alongside them for hours.

2019, BJP had a thumping win in the general elections. Unperturbed by the protests against demonetization, CAA, NRC, revocation of Articles 370 and 35 (a), Modi and co. were convinced whatever they did was the best for the future of the country. Foreign policy and economy were central to the government narrative amplified by a compliant media. Many pro-BJP channels floated bizarre theories, some suggesting that the newly minted Rs. 2000 notes had a nanochip fitted in them that would be helpful in curbing money laundering and terrorism.

Now, on May 19, just two years after COVID 19 hit the world and lockdowns paralysed economy, PM Modi, suddenly brings another firman to demonetise the “nanochip-fitted” Rs 2000 notes.

Over the last couple of years, Covid pushed the poor and the middleclass to the brink. Job losses and cash inflow slowed and business vanished overnight, this in addition to millions of lives that were lost.

New notes of 500 and 2000 introduced after demonetization was under the RBI’s act of 1934, Section 24 (1), which annulled Rs 1000 and Rs 500 notes.

Lofty claims were made that demonetization and the introduction of new Rs 2000 and Rs 500 notes would break the backbone of terrorism and curb money laundering and narcotics. None of that seems to have happened and now we’re faced with another problem that could put a common man in the same excruciating trouble that he had to bear with in 2016.

It won’t be an overstatement to say that demonetization is singularly aimed at scotching the cash flow of the opposition parties for the 2024 general elections.

Plastic and e-currencies through digital mechanisms are widely taking over. But we forget this country has over 70% poor who hardly have bank accounts, contrary to the government claims. Cash is still a way of life not only in India but worldwide. Digital mechanism of cash transfer is growing, but cash transaction still holds its place.

In 1977, Morarji Desai, after taking over as PM, took similar steps and I remember my father had to go to RBI in Calcutta to exchange the demonetized notes. When the 2016 demonetization happened, my father was bedridden and he recalled the sad days of the Morarji diktat and warned us of terrible times ahead. Well, he didn’t live long enough to see that himself, but he wasn’t off the mark.

Shome Basu is a Delhi-based senior journalist.