Rehman Rahi’s struggle to salvage the Kashmiri language is unparalleled.

Jaspreet Kaur

Language is the people. We cannot even conceive of a people without a language, or a language without a people. The two are one and the same. To know one is to know the other.

~ Sabine Ulibarrí

Language is the code we have to express the experiences of a people.

The nuances of the mother tongue remain just as smells of food that we have grown up eating. Julie Sedivy, author of ‘Language in Mind: An Introduction to Psycholinguistics’, writes: “When a childhood language decays, so does the ability to reach far back into your own private history. Language is memory’s receptacle. It has Proustian powers. Just as smells are known to trigger vivid memories of past experiences, language is so entangled with our experiences that inhabiting a specific language helps surface submerged events or interactions that are associated with it.”

Words, language have the power to define and shape the human experiences.

In the words of the renowned linguist, Joshua Fishman, when we take away the language of a culture we take away its greetings, its curses, its cures, its praises, its laws, its literature, its songs, its rhymes, its proverbs, its wisdom and its prayers.

The importance of languages cannot be undervalued. “It is the preservation of invaluable wisdom, traditional knowledge and expressions of art and beauty, and we have to make sure that we do not lose this,” says Lenni Montiel, UN DESA’s Assistant Secretary General for Economic Development.

Through the research of many linguists, psychologists and language educators, it has come to the fore that the effect of native language loss is far-reaching. It impacts familial and social relationships, personal identity, the socio-economic world as well as cognitive abilities and academic success.

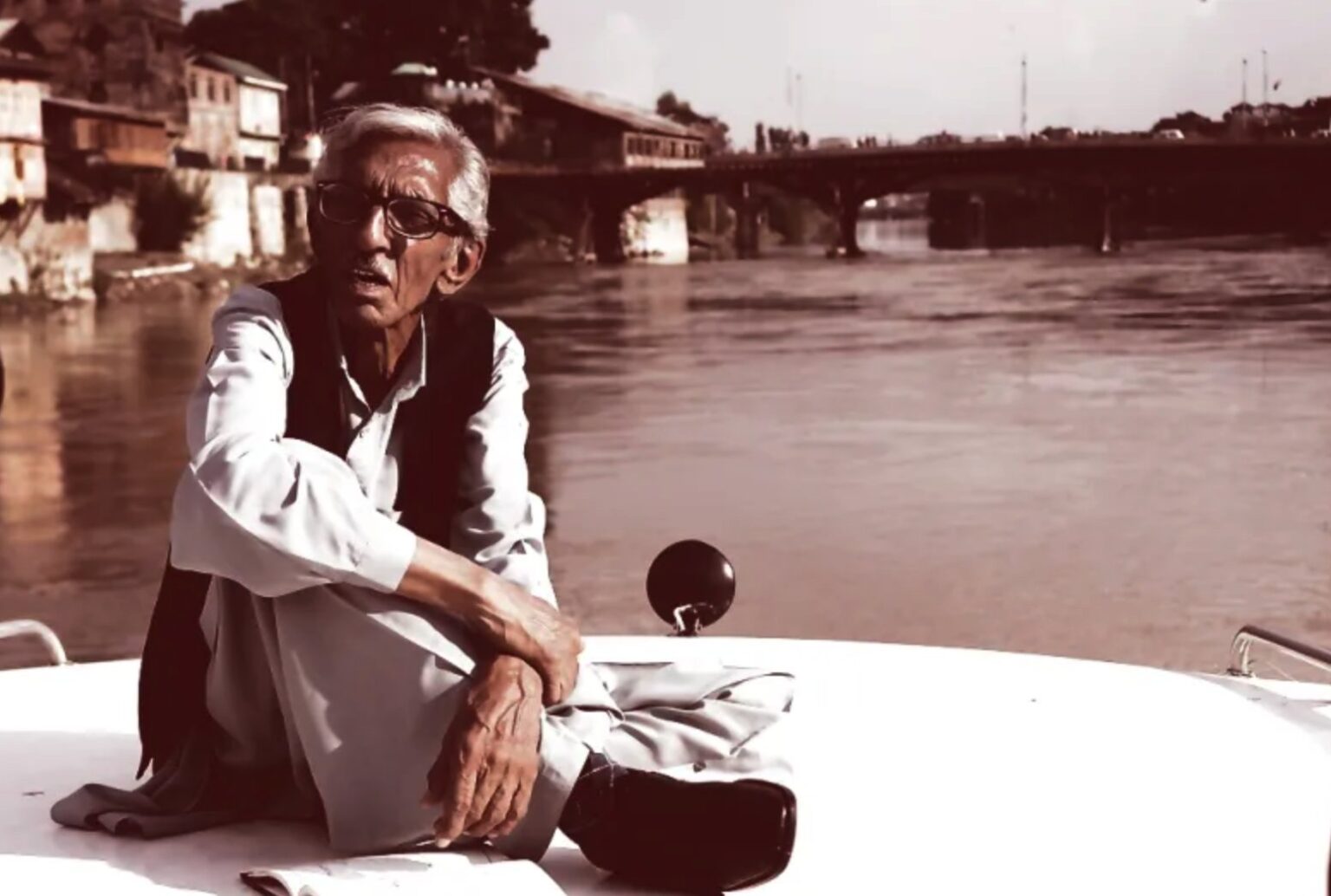

It is in this context that it becomes particularly important to remember the work of the renowned Kashmiri poet and critic, Rehman Rahi, winner of the Jnanpith Award and Sahitya Akademi Fellowship, who worked tirelessly throughout his life to salvage Kashmiri from the shadows of Persian and Urdu which otherwise dominated the Kashmir valley’s literary scene. Rahi passed away on 9 January.

His distinct approach to Kashmiri language and its adoption to convey universal themes remains unique. His legacy of having created his own idiom for his expression sets him apart from his contemporaries. His artistic accomplishments have expanded the imaginative and poetic world of Kashmiri language in an unprecedented way.

Numerous awards and publications came along the way as his poems continually express the philosophical musings of a mind firmly rooted in the valley.

Born in 1925, Rahi became the bastion of the Kashmiri language as well as its struggle to exist in its own land. He, however, remained largely unnoticed for most part of his life. I never heard a mention of him during any of the discussions that I have had with so many in Kashmir.

As is the case with most regional language writers and poets of the subcontinent, people, in general, rarely remain aware of their existence. At a function in Sopore, I had the chance to listen to Ghulam Nabi Pandit (Aatash), considered one of the biggest names in the Kashmiri folklore. Although I understood the gist of his recited poem, I missed the nuances which only a Kashmiri or anyone knowing the language would understand and appreciate. And that is why I don’t consider myself worthy of reviewing the works of the greats such as Rehman Rahi. I thought it befitting only to write on his work and mission to revive the Kashmiri language.

Aatash is also an expert on children’s literature that provides him the platform to promote the Kashmiri Language among the youth. His Kencha Mencha series for children has been well received in academic circles. In 2013, he wrote Kashir Shur Adbich Sombran, (An anthology of Children’s Literature in Kashmiri). He was awarded Bal Sahitya Puraskar for children’s literature in 2011. In 1981, together with S L Pardesi, he translated Russian poet Alexander Pushkin’s poems into Kashmiri. The book received Soviet Land Nehru Award for them in the same year. Aatash too remains unnoticed despite his tremendous contribution to Kashmiri and Urdu literature. Pained to see the present condition of the Kashmiri language, Aatash had said: “I have done my work for Kashmiri language and culture, now it is time for us to follow what we say.”

Rehman Rahi, when asked how he would like to be remembered, had said: “They should pay attention to the development of the Kashmiri language. That’s all. And if this language lives on, Rahi also lives on.”

Rahi believed that the Kashmiri language has been ignored by all political systems of Kashmir – from the Mughals up to the present times. In an interview published in Kashmir Lit in 2014, he said: “Kashmiri language has a very rich tradition. It is the most important language so far as the history of languages is concerned. There are people who say that it is as old as the Vedas… And so far as its creative potential is concerned, it has a very, very rich potential. You have the evidence in the form of Lal Ded and Sheik-ul-alam (RA) —a chain of great poets up to this time. So that way we should be proud of our language… Kashmiri language is a nation in itself by all means and by all angles. It has its own civilization and its own culture. But I don’t think Kashmiris are as conscious of Kashmiri language as they used to be earlier.”

Lamenting the maltreatment that the language has been subjected to, Rahi said: “There is a cultural onslaught on us. So we have to resist it and preserve our language. Not that we should hate or oppose other languages. We must learn other languages. For example, our younger generation must learn English. The more languages we learn and speak, the better it is for us; especially the English. But to start with, if we want to educate our young people and educate the nation in the real sense of the word, and if we want to have real concepts of things around us, that can be done only through our mother tongue.”

Rehman Rahi began his career as a clerk in the Public Works Department (PWD) of the government for few months in 1948 and was associated with the Progressive Writers’ Association, of which he became the General Secretary. He also edited a few issues of Kwang Posh, the literary journal of the association. He was later a sub-editor with the Urdu daily Khidmat. He did his M.A. in Persian (1952) and in English (1962) from Jammu and Kashmir University where he taught Persian. Later, in 1977, he joined the newly established Department of Kashmiri at the University of Kashmir where he taught till his retirement.

Rahi was on the editorial board of the Urdu daily Aajkal in Delhi from 1953 to 1955. He was also associated with the cultural wing of the Communist Party of Kashmir during his student days. Rahi translated Baba Farid’s Sufi poetry to Kashmiri from the original in Punjabi. Camus, Sartre and Dina Nath Nadim were some of the notable influences on his poetry.

Jaspreet Kaur is a Delhi-based architect, urban designer, Trustee Lymewoods & Span Foundation and Consulting editor of Kashmir Newsline.

(Please follow @KashmirNewsline on Twitter.)